Doctors with refugee status are a heterogeneous group of learners with unknown educational needs for entering new workplaces. Better processes for integration into the healthcare workforce may improve refugee doctors’ experiences and contribute to addressing the current healthcare workforce crisis. Simulation-based education has the potential to assist with refugee doctors’ integration, but this has not yet been studied. We describe a novel approach to co-creative action research for simulation-based curriculum development. This example may inform others who are developing curricula for learners with unknown needs.

The simulation curriculum was developed through collaboration with the Scottish Centre for Simulation and Clinical Human Factors, The Bridges Doctor Program both based in Scotland and Vital Anaesthesia Simulation Training. Over 1 year, teaching action research cycles (plan, act, observe and reflect) were employed at both macro (whole curriculum) and micro (single scenario) levels to develop a new simulation curriculum with refugee doctors. Written and verbal feedback from faculty and learners, in addition to field note diary entries, were collected throughout the process.

Eighteen refugee doctors participated. The resultant curriculum comprised 6 days of simulation-based learning, including an introduction to simulation, the systematic approach, multidisciplinary teamwork, collaborative decision-making and 2 days of acute medical emergency scenarios. Action research cycles influenced curriculum development at the macro level, for example, faculty learned how to use social media and concise pre-learning to maximize learner engagement. At the micro level, action research helped faculty to provide appropriate clinical knowledge sessions and change their approach to teaching behavioural skills.

Simulation curriculum development for learners with unknown needs is challenging. Taking a co-creative approach throughout development increased the likelihood that the curriculum priorities were truly agreed between learners and faculty. Social connections between learners and faculty played a significant role in the success of the simulation curriculum. The co-creative action research approach could be replicated by others involved in simulation development, particularly when learners’ needs are unknown or heterogeneous.

What this study adds:

•A deepened understanding of the learning needs of refugee doctors entering a host country’s workforce.

•Description of the construction of a simulation curriculum for the integration of refugee doctors into a new healthcare environment.

•Description of participatory action research methodology in the development of a new simulation curriculum.

•An alternative approach to Kern’s six steps to curriculum development for learners with complex and unknown educational needs.

•Reflection on the successes and challenges of simulation curriculum development using a co-creative approach.

Worldwide, refugee doctors face significant challenges during integration into the healthcare systems of their host countries [1]. The pathway to successful workforce integration is particularly arduous for this vulnerable group, with current processes inadequately preparing many doctors for work [2]. For example, in the United Kingdom, as in many other countries, refugee doctors must prove their qualifications, pass several exams and undertake a clinical attachment in order to obtain a medical licence. These tasks are more difficult for refugees who may have left their country on short notice without documentation or references, having experienced conflict and war, and possibly having spent years away from clinical practice [3,4]. Achieving official refugee status is a lengthy process, with prolonged periods of unemployment that erode skills and confidence [5,6].

Some refugee support schemes exist to provide education and orientation to the host country’s work culture [7]. Despite such schemes, refugee doctors are more likely to be referred for disciplinary action than their native-born counterparts [8]. Studies on the integration needs of refugee doctors suggest discrimination is common [1]. Refugee doctors also face challenges such as language exams and cultural differences [1,6]. While the elimination of discrimination is not the responsibility of refugee doctors to improve, bespoke training in language and culture would likely prove beneficial [9].

Simulation-based learning has been lauded for its ability to create moments of ‘cultural compression,’ allowing both the identification of values, beliefs and practices within a culture, and their transmission to learners [10]. Simulation ‘as a technique – not a technology’ [11] provides immersive, experiential learning that allows participants to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes in a safe and supportive environment [12,13]. Whilst simulation-based learning may be of theoretical benefit for refugee doctors, this has not yet been studied in practice. The development of a new immersive simulation-based medical education curriculum for refugee doctors may help to address the challenges of integration within their host countries.

Refugee doctors are heterogeneous group in terms of previous clinical experience and demographics. They represent a group with complex unknown learning needs, which if optimally supported, could address issues of wasted talent and workforce deficiencies. When learners’ needs are unknown to curriculum designers, the construction of an effective, relevant and engaging simulation curriculum can be challenging. Common approaches to simulation curriculum development include Kern’s six-step model [14]. This model assumes that learning needs are easily established early in the curriculum development process, through means such as consultation with learners via pre-curricula survey [15]. This may be an effective approach when learning needs are known, or when learners have insight into their needs, but a different approach is required when learning needs are unknown. The use of co-creation in simulation curriculum development may pose one solution. Co-creation of research can be defined as ‘the collaborative generation of knowledge by academics collaborating with stakeholders’ [16]. Co-creative processes in service design, public health, and educational contexts, purport benefits including better prioritization of needs, along with self-efficacy and empowerment of stakeholders [17,18]. Co-creative curricula can positively impact identity development and lead to improved assessment performance [19]. The literature suggests that co-creative processes that are carefully planned, iterative and focus on building sustainable relationships are more effective than teacher-centred approaches [17]. Simulation curricula that utilize various learning strategies and integrate them with current programmes are shown to improve learning [20]. The approach to the development of a co-creative simulation-based educational curriculum has yet to be explored.

This study aimed to:

1.Co-create an immersive simulation curriculum for refugee doctors to help them integrate into their new healthcare systems in the United Kingdom.

2.Describe our co-creative process for developing a simulation curriculum, for learners with unknown needs, so it could be used by other simulation course developers.

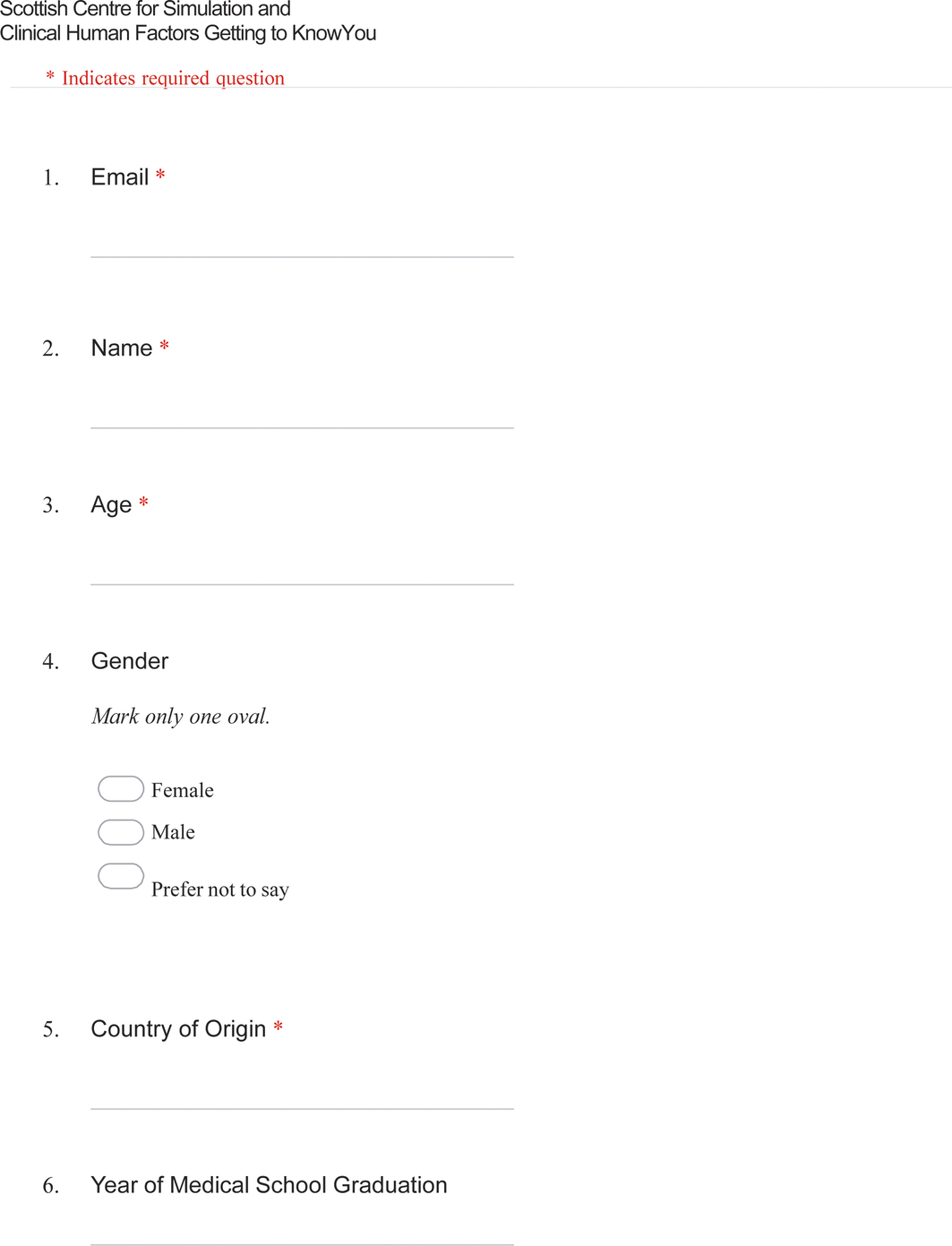

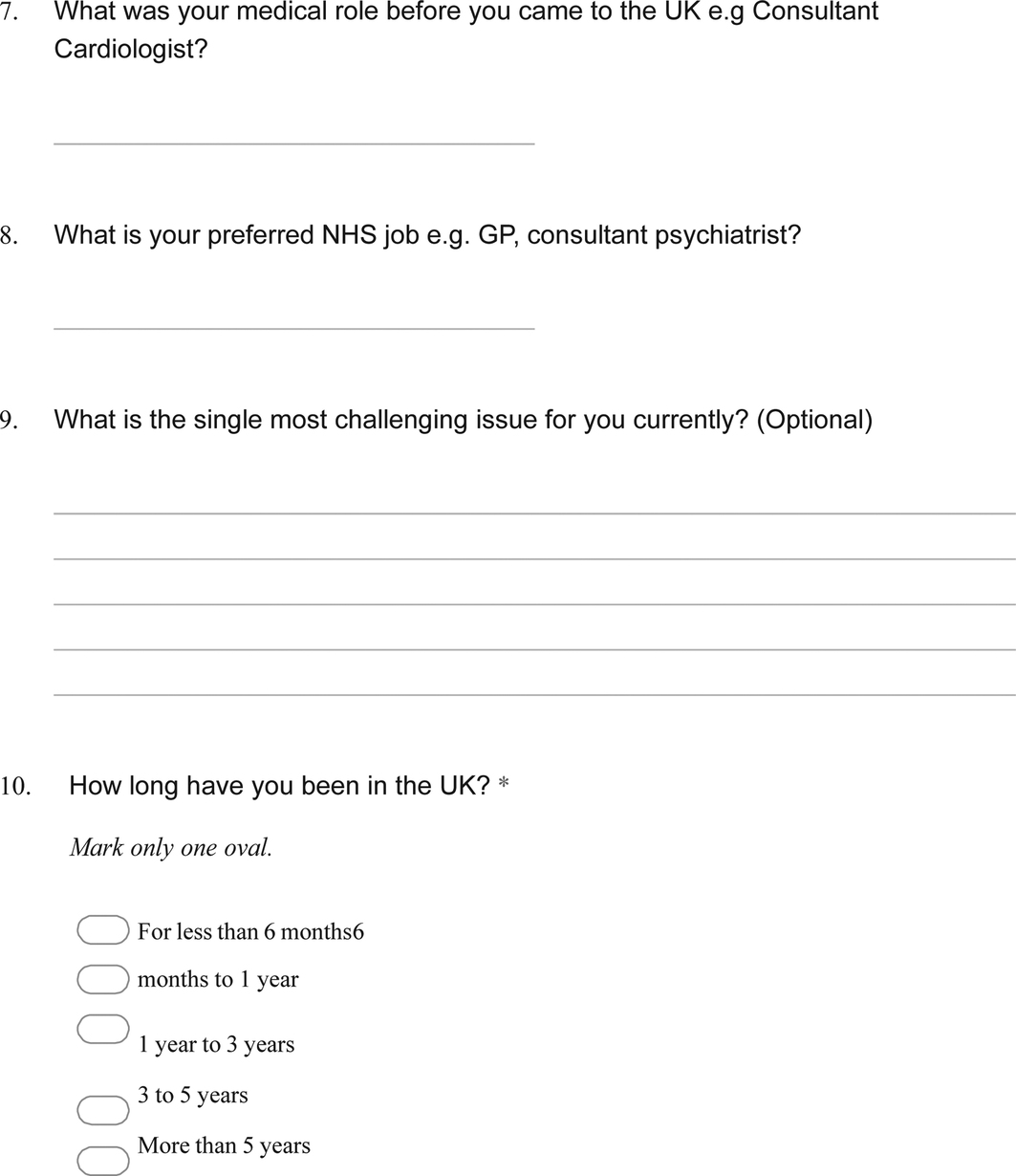

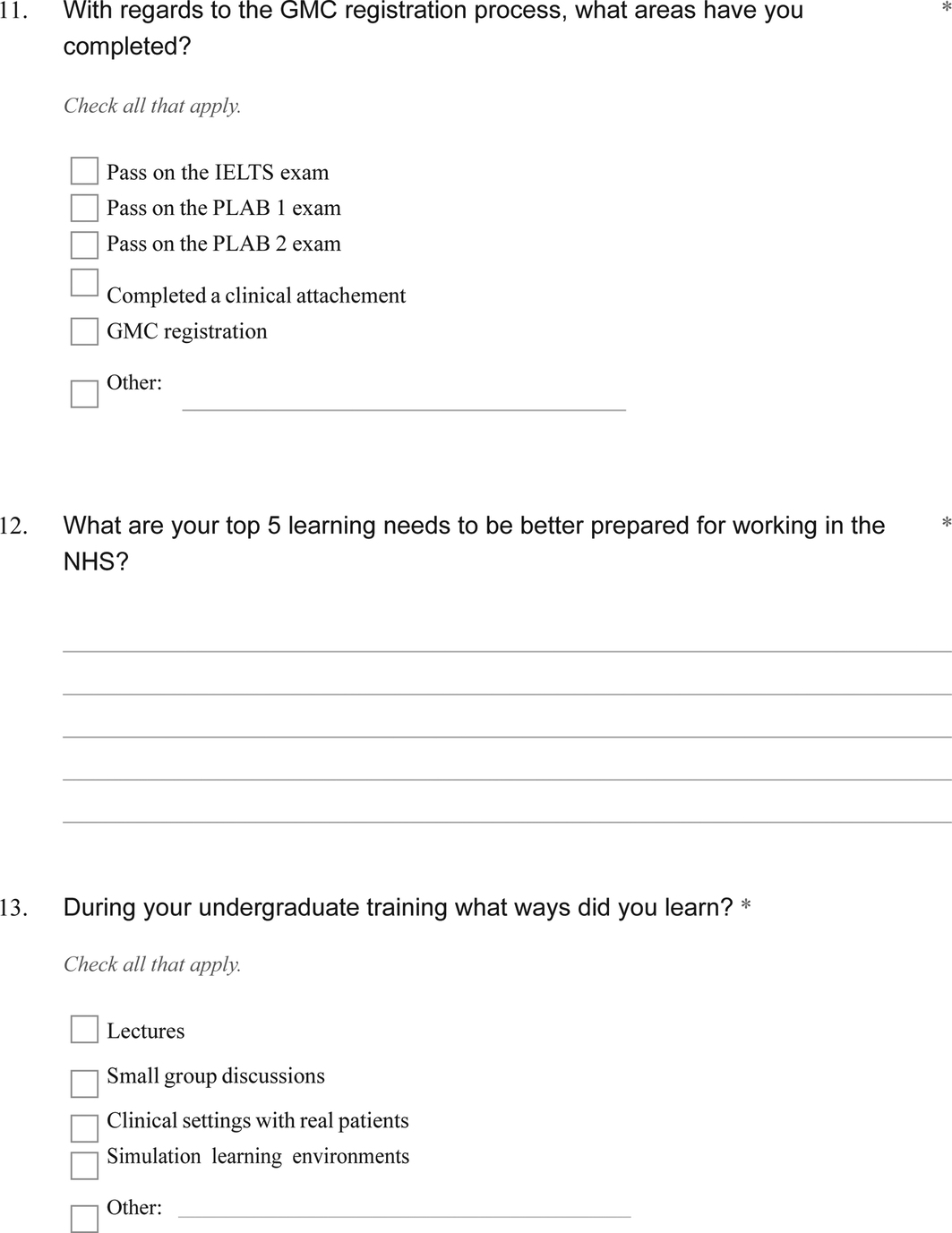

The need for full ethical approval was sought and waived by the Forth Valley Royal Hospital Research and Development department. The project was registered under the hospital quality improvement department and Caldicott guardianship approval was granted. Participants were asked to complete a voluntary electronic questionnaire on their background at the start of the course.

In this study, we took a subtle realist stance, in which we viewed reality as existing independently of the researchers. We acknowledged that our knowledge of the world was constructed between researchers and the refugee doctor cohort [21]. The cohort was heterogeneous with regards to their prior clinical experiences and their learning needs were unknown. We therefore used action research methodology to develop the simulation curriculum. The underlying philosophies of co-creation and action research are similar as democracy is fundamental to both. Action research was first proposed by a refugee in the 1940s fleeing Nazism and developed by Lewin in 1946 as a research method to ‘improve social formations by involving participants in a cyclical process of fact finding, exploratory action and evaluation’ [22]. We used a type of action research called the teaching action research model [23]. This model employs cycles of planning, acting, observing and reflecting.

Co-creation is an umbrella term describing a number of different processes outlined in Bovill’s typology of co-creation which includes initiation, focus, context and scale [24]. Within our study, co-creation was initiated by faculty. Some of the refugee doctors acted as consultants, whereas others were co-designers. Table 1 shows the parameters of co-creation according to Bovill’s typology and how our approach aligned with the parameters. The refugee doctor cohort was engaged as learners, pedagogical consultants and co-designers of the simulation curriculum.

| Bovill’s typology | Possible options | Application in this programme |

|---|---|---|

| Initiator | Staff-led Student-led Both staff and students |

Staff-led (initiated by faculty) |

| Focus | Entire curriculum Learning and teaching Educational research and evaluation Disciplinary research Wider student experience |

Entire (simulation) curriculum |

| Context | Curricular Extra-curricular University-wide |

Curricular |

| Number of students | 1–5 6–10 11–20 21–30 31–100 101–500 |

18 |

| Student selection | Selected students Whole class/ group |

Whole group |

| Timing | Retrospective Current Future |

Current |

| Student year | Year 1 (undergraduate) Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Masters PhD |

Qualified doctors at various levels of further education |

| Scale | 1 class Several classes 1 project Several projects Faculty/ school-wide Institution-wide |

Single project |

| Duration | Days Months Years |

Several months |

| Role of students | Representative Consultant Co-researcher Pedagogical co-designer |

Some were pedagogical consultants; others were pedagogical co-designers |

| Nature of student involvement | Informed Consulted Involved Partners Leading |

Consulted and involved (but not leaders) |

| Reward or recompense | Payment in money Payment in vouchers Course credit No payment Refreshments |

No payment |

| Reason | To improve course To enhance student engagement Aiming for social just higher education Impressed by benefits Want student perspectives To enhance student’s skills |

To improve the course, enhance student engagement, and required learners’ perspectives |

The Scottish Centre for Simulation and Clinical Human Factors (SCSCHF), the national simulation centre for Scotland, was approached by a charity based in Glasgow, The Bridges Doctors Programme. The charity aims to help refugees, asylum-seeking, migrant doctors, or any doctors in Scotland for whom English is a second language, to integrate into the healthcare workforce. The SCSCHF was asked to develop and deliver a simulation programme to support refugee doctors in preparation for undertaking their first clinical attachments prior to full employment.

The SCSCHF delivers varied immersive simulation experiences for multi-disciplinary learners, at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. It is a fully equipped simulation centre, which includes a variety of adult and child manikin simulators, monitoring and resuscitation equipment, ward paperwork and protocols. Scenarios are continuously video- and audio-recorded and played live to observing participants. The SCSCHF partnered with the Vital Anaesthesia Simulation Training (VAST) [25] team, who provided expertise and input into the curriculum design.

The refugee doctors were referred from the Bridges Doctors Programme to attend the SCSCHF on a volunteer basis, before entering clinical practice in Scotland. They can be considered a convenience sample. We did not have an active role in the selection of the 18 doctors in this cohort. During the first face-to-face meeting, the doctors were asked to consent to the role as learners and pedagogical consultants in the co-creative programme development.

When developing the curriculum, we followed the ‘plan, act, observe and reflect’ cycle of the teaching action research model. We used this cycle on both a macro level (such as the prioritization of curriculum content overall) and micro level (such as scenario iterations).

Initial planning involved collating a team of simulation designers from the SCSCHF and VAST to identify the preliminary goals of the project and relevant broad themes through organized online meetings. The broad themes were shown to the refugee doctor cohort at face-to-face meetings, opinions were gathered and feedback was provided to the design teams by JD.

In the planning phase, we aimed to improve our understanding of the issues faced by refugee doctors, to improve our understanding of the individual learners in the programme and to make decisions about the educational focus of the programme. The methods used to fulfil these planning aims are shown in Table 2.

| Planning aim | Methods used |

|---|---|

| To improve researcher understanding of the issues faced by refugee doctors | 1. Initial literature search to explore the experiences and needs of refugee doctors. 2. Informal interviews with four experts who have worked with and supported international medical graduates and refugee doctors, to understand the perceived needs of this group. 3. Informal interviews with refugee doctors who currently work in the National Health Service (NHS), with a focus on required areas of support that remain unaddressed. |

| To improve researcher understanding of the individual learners in the programme | 1. Voluntary electronic questionnaire to gather background information on the specific learner group in the programme (see Appendix 1) 2. Focus group with the learner group (18 participants) on the first day of the course, to explore the question ‘What do you feel prepared for and unprepared for, to the to start work in the NHS’. This allowed insights into potential topics to cover in the curriculum. 3. Social media such as WhatsApp used to connect the faculty and learners outside of the organised sessions and garner any unmet needs. |

| To make decisions about the educational focus of the programme | 1. Creation of a simulation team with design and delivery expertise. We collaborated with simulation experts with some previous experience of similar learner groups (e.g. working with doctors from low-resource settings). We also incorporated a clinical psychologist on the team, to help inform sensitive course design decisions. 2. From the start of the project an NHS doctor with refugee status, has contributed to the project in the role of researcher, designer and faculty. 3. Our initial content was based on the Scottish Centre for Simulation and Clinical Human Factors undergraduate and Vital Anaesthesia Simulation Training curricula, parts of the United Kingdom Foundation programme curriculum (for newly qualified doctors) and the experiences of the simulation team working with doctors from low-resource settings. This initial topic list was reviewed by the refugee doctors during the introductory session, their opinions were sought and modifications were made. |

While the themes and the topic content were identified earlier in the development of the curriculum, the learning objectives and structure of the sessions were developed after the delivery of the previous session. This allowed for the opinions of the learners to be sought and incorporated into the programme development from the first meeting onwards.

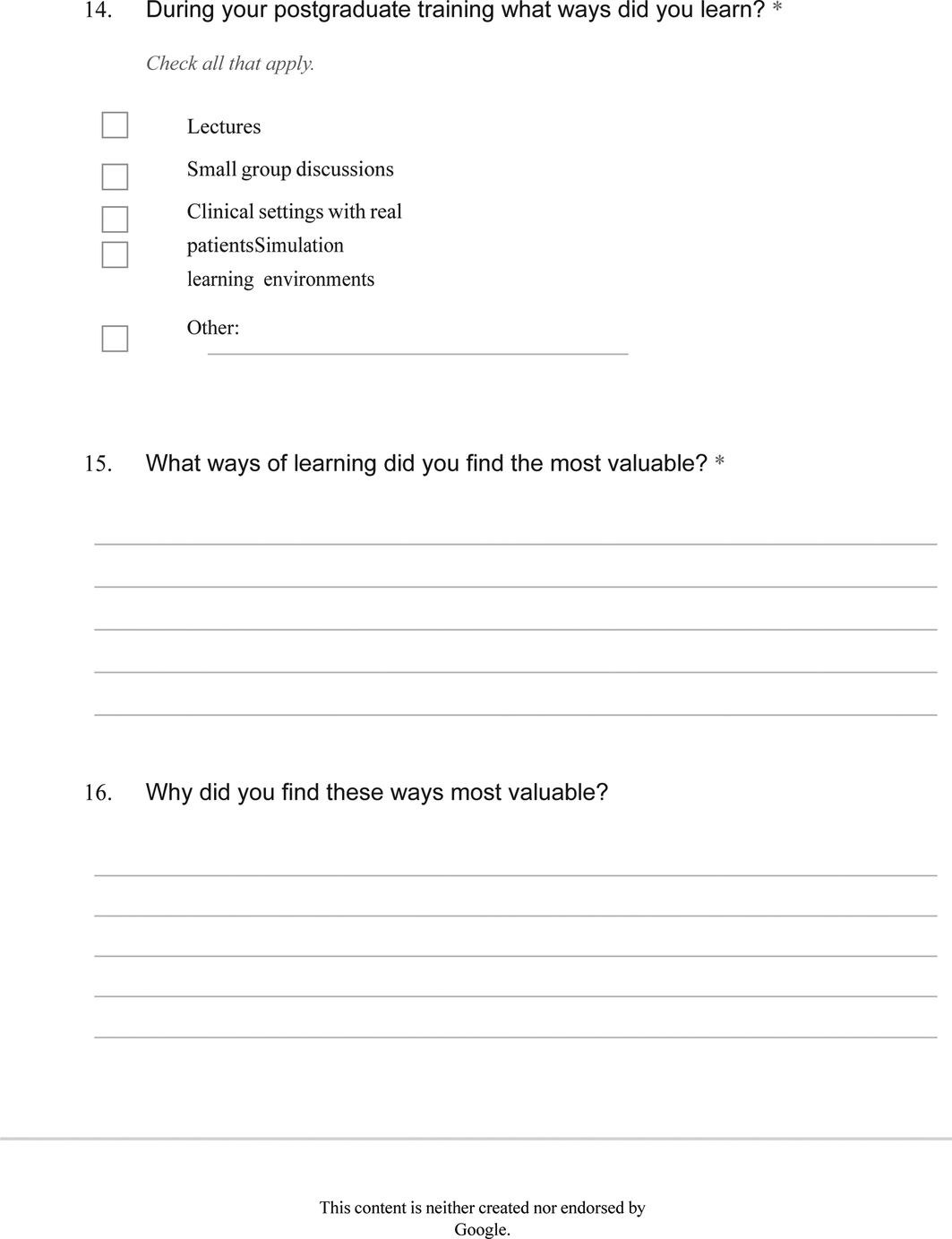

These specific learning objectives were co-created through the initial focus group discussions and ongoing written feedback from the cohort (see evaluation form, Appendix 2). Topics were discussed with the learners throughout the delivery stage and feedback mechanisms allowed for reflective input from the faculty and the learners. At the end of every face-to-face session, time was allocated for reflective group discussion on the day and for faculty to listen to the refugee doctors’ opinions, including ideas on specific content, experiences with the programme and upcoming training planned. JD recorded electronic whiteboard notes and field notes. At the end of each session, written feedback from the cohort was gathered. Further opinions on the overall experience of the simulation curriculum were offered through a WhatsApp group.

The simulation design team, from Canada and Scotland, created simulation scenarios based on the co-created learning objectives, and the Scottish team delivered the scenarios. The simulation debriefs employed the Scottish Centre Debrief Model [26].

We developed six sessions over the course of 1 year (Table 4). Eighteen participants in total completed the course in the first year. The cohort of 18 was divided into three sub-groups of 6 to optimize the simulation experience. Each session was therefore run three times, each with a different group of learners. This approach allowed for test-and-retest as part of the action research cycle.

We sought faculty reflections and requested written and verbal feedback from the cohort after each simulation course day. The programme lead (JD), who engaged in both design and delivery, attended all sessions and kept a field note diary. We observed the learners’ behaviours during the simulation scenarios and watched group interactions closely. We retained a written record of the debriefing ‘take home messages’ (group reflections about their learning for the day) to provide some information about whether the cohort’s learning matched the intended learning outcomes.

We reflected on all the observations collected (above) to iteratively improve the course, thus triggering another cycle of action research.

We scrutinized each simulated scenario using the ‘plan, act, observe and reflect’ action research cycle, running each scenario three times and making improvements where necessary. The lead researcher (JD) took field notes of the micro-level changes throughout curriculum development. Examples of changes made are given in the results section.

The research group consisted of doctors with backgrounds in anaesthesia, general practice, accident and emergency, and acute medicine. Our educational backgrounds include simulation-based medical education in both high- and low-resource settings. Our team included researchers from Scotland, Turkey and Canada. One of the researchers was herself a doctor with refugee status. Despite our diverse backgrounds, we all held beliefs that simulation-based education would be the mode of delivery that would provide the greatest benefits to our learners, likely as a result of our own experiences as both simulation participants and facilitators. Our experiences facilitating simulation in low-resource settings have emphasized to us the value of behavioural skills teaching, which has likely informed the incorporation of these elements.

The cohort comprised 18 doctors (15 women and 3 men) who held either refugee, asylum-seeking, humanitarian protection, or other migrant status. The age range was 26–49 years. Further demographic data are shown in Table 3.

| Length of time in the United Kingdom | More than 5 years | 9 |

| 3–5 years | 5 | |

| Under 3 years | 3 | |

| Undisclosed | 1 | |

| Country of origin | Afghanistan | 1 |

| Azerbaijan | 2 | |

| Iraq | 2 | |

| Libya | 2 | |

| Pakistan | 3 | |

| Sudan | 4 | |

| Undisclosed | 4 | |

| Clinical background | No postgraduate experience | 3 |

| General clinical experience | 1 | |

| General practice | 3 | |

| Medical specialities | 4 | |

| Surgical specialities | 3 | |

| Radiology | 2 | |

| Undisclosed | 2 | |

| UK medical license progression | Passed English language test | 6 |

| Passed clinical knowledge test | 7 | |

| Passed clinical examination | 7 | |

| Completed observership | 2 | |

| License to practice medicine | 4 |

Over the course of a year, we developed a 6-day simulation course for doctors who were soon to undertake a clinical attachment. The course aimed to increase awareness and understanding of several key areas around the role of a newly qualified doctor. The course structure took a spiral learning approach, in which each participant was encouraged to use previous course content to apply to the next session [30]. The level of challenge increased as the course progressed. The immersive simulation scenarios required scaffolding with pre-learning materials and group activities. Several studies suggest increased learning efficacy when different educational strategies are employed within a simulation curriculum [20]. Our approach is discussed in the action research macro-level example in the Aim 2 results. A summary of the full curriculum, after three action research cycles, is shown in Table 4.

| Content covered | Rationale for content |

|---|---|

| Day 1: Introduction to simulation | |

| • Introduction to simulation learning environment and the simulation team • Opportunity to meet the learners and understand their background and goals • Building a learning contract • Setting out the importance of psychological safety |

We found that the approach to learning using simulated environments was a new experience of all participants. The learners’ previous experience usually involved a didactic approach with little experiential learning. We needed to explain exactly what we meant by ‘simulation’ and what we expected of the learners. This session also incorporated the needs assessment as laid out in Table 1. |

| Day 2: Developing a systematic approach | |

| • The A to E approach [27] • Standardised communication for handover of unwell patients: Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) [28] • Skills stations: Basics of oxygen delivery and basic airway manoeuvres. • Application of A to E, basics skills and SBAR in management of septic patient on a medical ward and hypoglycaemia simulated scenarios |

In the United Kingdom, the A-E assessment is a commonly used standardised approach to performing a priority-driven clinical examination for critically unwell patients. We found that this was new to the learners. The learners were also unfamiliar with a structured handover communication approach. We taught these skills in the classroom then practised within simulated scenarios. We introduced the oxygen delivery and basic airway manoeuvres, which are essential priority skills for safe management of sick patients. We also explored the equipment and resources available in the NHS. |

| Day 3: Multidisciplinary team (MDT) working | |

| • Introduction to the MDT • Importance of MDT for safe patient-centred care • Roles within the MDT • Scenarios involving learners as newly qualified doctors working in the ward MDT |

Most learners had little to no experience of MDT working, the varied roles with a typical team and expectation of the doctor within the UK MDT. A classroom knowledge session was followed by experiential learning in scenarios, which allowed the learners to develop skills in teamwork, prioritization and communication as well as starting to build an understanding of teams and care structures within the NHS |

| Day 4: Collaborative decision-making | |

| • Introduction to type 1 and type 2 thinking [29] and impact on clinical decision-making • Introduction to the impact of stress on cognitive function and psychological strategies to manage decision making under pressure with simulation team psychologist. • Introduction to ethical concepts such as patient consent, confidentiality, capacity decisions, anticipatory care decisions and patient-centred care • Three simulation scenarios exploring capacity, escalation of care in unwell patients including palliation and communicating clinical decision-making |

The role and expectations of the foundation doctor and ethics in patient-centred decision making in the United Kingdom is culturally hugely different from many in the cohort. Building awareness of various legal and ethical standards, and using simulation to explore the approach, allowed the doctors to start to develop a working understanding of ways to provide patient centre care. |

| Day 5: Integrative care across the NHS: the newly qualified doctor role, part 1 | |

| Synthesizing the learning experience from the previous course days, this day consisted of four simulated scenarios involving acutely unwell patient management in primary and secondary care. The medical pathologies were some of the most typical UK presentations such as myocardial infarction and alcohol withdrawal. | The needs assessment highlighted challenges in understanding the complex NHS systems including the structural integration between primary and secondary healthcare and the interface between the two. Management of acutely deteriorating patients allowed repeated simulation practice in systematic assessment, specific behaviour skills and communication. Many of the doctors felt unprepared to manage common disease presentations found in the United Kingdom, so these scenarios allowed for rehearsal in a safe learning environment and increased understanding of the role of a newly qualified doctor. |

| Day 6: Integrative care across the NHS: the newly qualified doctor role, part 2 | |

| The final day of the course content had a similar structure with different medical pathologies, common in the United Kingdom. The scenarios were the most challenging, for example paediatric meningococcal sepsis. The scenario took place in the paediatric ward where the participant should work with the MDT, including roles such as the paediatric advanced nurse practitioners, and critical care team to stabilise the patient and consider transfer to higher-level care. | These scenarios were more challenging and required the participant to synthesise all of the knowledge and skills learned in the earlier parts of the course. |

The refugee doctors played a pivotal role and contributed widely to the development of the curriculum. Table 5 gives examples of the ways in which co-creation influenced curriculum development. These examples are not exhaustive but are illustrative examples of the ways opinions were sought and how they influenced changes.

| Co-creative input | Description of input | Action | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input from the researcher and faculty member who has refugee status | Refugee doctors highlighted the challenges of learning new abbreviations in medical note documentation and understanding local dialect. | Refugee doctor researcher, SIU, designed a session on language and NHS culture as an icebreaker on the second day of the course. She delivered this session initially and supported other faculty to run session subsequently. Resources, including a social media support group for international medical graduate doctors, were shared. |

These factors positively improved relationships and psychological safety early in course. The content was valued immensely by learners. |

| Input from refugee doctor cohorts as pedagogical consultants through written feedback | An example written feedback after multi-disciplinary team session was, ‘I liked the communication skills, how to manage the situation, never been taught about MDT [multi-disciplinary teams] in a very real way’. | This individual’s feedback was shared with the faculty on the day and feedback to the research team by JD. | This allowed the researchers to build confidence in the value of simulations as the method of learning. |

| Further written feedback after multi-disciplinary team session ‘You are doing amazing, keep it up and have more patient centred scenarios’. | This individual’s feedback was shared with the faculty on the day and feedback to the research team by JD. | The fourth session focussed on shared decision-making in regard to anticipatory care planning. | |

| Several learners requested ‘scenarios on emergency cases’, ‘opportunities to practice with emergency guidelines and protocols’ and to build a greater ‘understanding of the National Health Service structures’. | This feedback influenced the design team to create two sessions dedicated to management of acutely unwell patient in primary and secondary care. | The learners were able to synthesis learning from the previous course days and practice and build their confidence in emergency scenarios within the NHS | |

| Input from refugee doctor cohorts as pedagogical consultants through verbal feedback | Learners on the systematic assessment day wanted more time to practice A to E assessment | Faculty adapted the sepsis scenario to be less immersive and more of a supported walkthrough simulation with faculty and learners discussing and roleplaying as the scenario progressed. Later iterations added peer practice and A to E handouts. | Learner needs were more effectively addressed with regards to basic assessment of unwell patients. |

| The learner cohort asked for more support to manage stress in exams. | Debrief with learning objectives including stress management were incorporated. A session with our team psychologist on stress management was development for decision-making day. This was positively received by the group. |

Learner needs beyond medical education were addressed for example doctors reported positive change in identity and social bridges of integration after participating in the course [9]. | |

| In the introductory session, the learners requested access to care management protocols across a wide variety of topics. | Selected protocols and guidelines relevant to course content were developed as pre-learning and discussion before scenarios to scaffold learning. | Learners were able to perform in the simulation scenarios because knowledge gaps had been addressed. The pre-learning could be referenced by the learners as needed in their own time. |

We applied the action research cycle (plan, act, observe, reflect) to the curriculum development in several different ways. Below we give an example of how we employed action research at the macro level (i.e. whole curriculum level), constructed from the field notes of the principal researcher and co-creative feedback methods.

Based on our experience in diverse global settings, we suspected that the learners would be unfamiliar with immersive simulation and anticipated that extra effort would be needed to create a psychologically safe learning environment. We planned to create a reflective and open environment, pitched at the optimal level of challenge, to increase learner engagement. During the initial sessions, we observed that our concerns were well-founded. It took several visits to the centre before the refugee doctors became more open and reflective in debriefing and more forthcoming with their opinions. When the refugee doctor cohort attended the sessions, they were very engaged but challenges such as late attendance, last-minute cancellations and failure to prepare the pre-learning before the session occurred frequently.

We found the issues of late attendance and failure to complete pre-learning frustrating, but we reflected on the importance of understanding the cohorts’ experiences more deeply to find potential answers. We planned a brief group discussion to explore the reasons for not preparing the pre-learning for the sessions. The refugee doctors cited difficulty in finding time and cognitive bandwidth to adequately prepare for the sessions. There were complex competing demands on their time and attention, such as childcare, financial stress and legal challenges relating to asylum applications, employment or housing.

Consequently, we agreed as a group to reduce the required time spent on the pre-learning to a maximum of 30 minutes, prioritize some reading as essential and others as optimal and provide the pre-learning for the entire course at the beginning so that learners could access material at a time suited to them. The open discussions helped to build a positive relationship between the faculty and the refugee doctor cohort. We observed their disclosures about personal challenges as markers of increased psychological safety in our group. More people were able to complete the pre-learning material as the course progressed compared to the initial two sessions.

The challenge of lateness and last-minute cancellations remained present. We therefore discussed the best modes of communication with the group. Email did not seem to suffice so we set up a social media group chat (WhatsApp) with one faculty and the learners. The group could be used to confirm attendance in the run-up to the sessions, communicate transport issues on the day, and remind learners of pre-learning or other email communications. We observed much better engagement with communication through the WhatsApp chat. People asked more questions about the course and reflected on their experience of the sessions. Lateness was not completely prevented but improved.

The WhatsApp group played a beneficial role in organizational aspects of the curriculum. Furthermore, it seemed to build greater rapport with all members of the group. We hypothesized that the refugee doctor cohort perhaps used WhatsApp regularly and thus it was familiar and felt more informal. Being in a group of any kind encourages members to be more accountable for their behaviours and communication. This simple communication tool clearly improved engagement.

In the following two examples, we provide details of how we used the action research cycle at the micro level (level of a single scenario design).

We designed a scenario for the identification and management of myocardial infarction, based on the request for this topic from refugee doctor cohort in the introductory session. For the first group in this session, the simulation delivery team observed that the learners could not accurately interpret the electrocardiogram (ECG) findings. When this occurred, the clinical decision about initial management could not be made and the scenario took an unplanned path, requiring reactive input from the simulation team to support learning and progress through the constructively aligned scenario. The team reflected that the ECG was too complex and that a simpler example may help.

For the second group, we planned the same scenario, with a straightforward ECG that we thought would be easier to interpret. The scenario, including the simple ECG, was delivered to this second group. Unfortunately, they were unable to interpret the ECG or complete the scenario without significant support. We reflected that together we, the researcher and the refugee doctor cohort, had made incorrect assumptions about ECG interpretation abilities. The refugee doctors had reported confidence in their abilities to diagnose the disease when we explored learning needs at our first meeting.

For the third group, we discussed ECG interpretation with the learners before the scenario, including a short tutorial to establish baseline knowledge and to highlight examples of normal and abnormal findings. This group was able to interpret the ECG and able to complete the scenario without further support from the simulation team. Following this session, the simulation ran smoothly, and the ‘take home messages’ (learning points identified at the end of the sessions) were better aligned with the learning objectives of diagnosis and management of myocardial infarction, rather than the generic learning points expressed by the previous groups. We reflected on the value of simulation to address learning needs and the challenge in truly eliciting these needs from a heterogeneous group early in the curriculum development process when social pressures might result in over-estimation of one’s abilities.

We, as researchers, made assumptions that the refugee doctor cohort would have little previous behavioural skills training and we planned to introduce the concepts at the beginning of the curriculum. For the first group in this session, we used a short video clip in which a passenger aeroplane makes an emergency landing in the Hudson River. We asked the learners to observe the dialogue between the pilots and to consider aspects that contributed to the success of the rescue. After watching the clip, we debriefed the group on their observations and tried to relate the behavioural skills to those of health professionals. The group found the movie clip to be interesting, but their comments suggested that they had not appreciated the advanced behavioural skills displayed by the pilot and team. We reflected that, while the movie clip was engaging, it did not achieve the learning goals because the learners struggled to see the relevance of their healthcare roles.

For the second group, we changed the video clip to the Resuscitation Council ‘A-E assessment in the deteriorating septic patient’. We ran the session again, asking the same signposting questions as with the previous session, and again debriefed the group. We observed a more in-depth discussion on behavioural skills with less prompting by the facilitators. The learners were able to focus more on the specifics of teamwork or decision-making. However, when debriefing the group, we saw that the example behavioural skills demonstrated in the video were not always role-modelling good behaviours. When learners are becoming aware of new concepts, they do not necessarily have the ability to discriminate between levels of competence.

For the third group, we considered a more experiential activity. The literature suggests serious game simulations play a beneficial role in the development of technical and behavioural skills [31]. We worked with our simulation collaborators, the VAST group, who used a game as an icebreaker and an introduction to behavioural skills. The game required the group to move around the room and work together to play catch and keep three objects (representing different care priorities) in the air for as long as possible. We then debriefed the group on their team’s performance in the game, asking them to play it twice, so that they could try out the behavioural skills they had identified from the debriefing. The group responded positively to the experience with laughter and lots of communication. During the debriefing, they identified more specific ways to improve behavioural skills, with suggestions such as team delegation, using peoples’ names when communicating and considering situation awareness.

This game simulation was powerful in several different ways. We were looking to find a way to effectively introduce the relevance of behavioural skills to the refugee doctor cohort and convey the idea that behavioural skills are trainable using simulation. We felt the game achieved this. We noticed additional benefits in terms of earlier flattening of the hierarchy between learners and faculty and continued enhancement of psychological safety within the group. Being debriefed on the behavioural skills game started to frame the concept of reflective learning as an informal and non-judgemental facilitated discussion.

This study demonstrated how a simulation curriculum for the integration of refugee doctors into new healthcare systems was developed through co-creation. In our opinion, traditional approaches such as Kern’s six stages of curriculum development are not appropriate to use for diverse groups of learners with unknown needs. Kern’s model incorporates a targeted needs assessment, that can be revisited, but usually, this forms step two of curriculum development, before designing the curriculum. For a heterogeneous group such as ours, a brief period of needs assessment would not have sufficed. We needed a more fluid approach that allowed relationships between the researchers, faculty and refugee doctor cohort to build and allow for reciprocal agreement on achievable goals of the simulation curriculum. In this sense, there was a blurring of lines around co-creative roles between researchers and the refugee doctor cohort as we all learned together about cultural contexts and previous training experiences.

We realized there was a limited benefit in asking the cohort about learning needs early on when they had an incomplete picture of the expectations for working in the National Health Service. By developing the curriculum together, we learned about the complexity of their needs and the refugee doctor cohort developed a clearer picture of expectations for their future.

Our novel co-creative approach to simulation curriculum development allowed us to optimize the design and delivery of a curriculum for our heterogeneous group of learners. The action research methodology cycles formed the key approach adopted to optimize the co-creative process. We have demonstrated, with our examples, how the cycles can be applied to iterative development of curricular goals such as maximizing learner engagement, and on smaller scales for simulation scenario efficacy.

One of the main benefits of the co-creation process used to construct the simulation curriculum was the redistribution of power between facilitators and learners. The use of action research methodology was beneficial in this regard because employing structured cycles actively encouraged all of us to think more deeply about challenges. It used a more analytical approach involving the whole-group opinion rather than making assumptions about learning needs. Our experiences are mirrored by research, well described in the literature, around participatory action research which looks to involve all members as co-researchers [32,33]. The move away from more traditional, researcher-centric methods of research, to uncover new knowledge, was particularly relevant to the development of a curriculum with unknown learners. However, using action research cycles alone could not overcome the existing hierarchy in our co-creative process.

The idea that co-creation should be ‘a collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants can contribute equally but not necessary in the same ways to curriculum development’ [19,34] was difficult to truly realize. Social power, the ability to use ‘one’s will to affect thoughts, emotional and actions of others around us’ [35], is the underlying concept at play in hierarchical group dynamics such as medical learning environments. Despite our efforts to reduce the hierarchy, in our group, the simulation team remained in a greater position of power in several ways beyond the hierarchy of the teacher–learner relationship. The faculty trained and worked in the healthcare system the refugee doctor was hoping to join, thus possessing the knowledge and experience desired by the learners. The refugee doctor cohort held intersectional characteristics such as female gender and black or ethnic minority race. Being international medical graduates, they were more likely to have an expectation of a traditional approach to learning, where values are rooted in respect of hierarchy and behaviours such as questioning or challenging the teachers’ knowledge are discouraged [36]. In this study, we found that the process of co-creation could occur despite the co-existence of an ingrained hierarchy.

Building strong social connections is inherent to the process of co-creation. During the process, we prioritized social connections, including bonds (connections amongst the cohort) and bridges (connections between the cohort and faculty). Both bonds and bridges are thought to be important for refugees’ social integration [37]. We found that bonds amongst participants occurred naturally, but bridges between faculty and participants required more effort. Initially, the participants were quiet and formal, consistent with their prior experiences in medical training. The simulation learning environment and the ethos of the simulation faculty were unfamiliar. The refugee doctors were surprised at being consulted about how to organize curriculum content or logistical issues, such as how to structure the day around time to pray or finishing time for mothers who had childcare commitments. Many of the refugee doctor cohorts were initially reserved and let the more confident members speak for the group. This posed a challenge for us as researchers to develop a deep understanding of their perspectives.

To increase social bridging connections, we drew on the psychological safety literature. We consistently demonstrated implicit and explicit behaviours that Kolbe et al. highlight as important to optimize psychological safety [38], such as being authentic, reflective and curious to understand the cohorts’ experience and perspectives. We repeatedly attempted to normalize mistake making and showed ourselves to be vulnerable as learners in this co-creative process. Our other strategies for improving social connections are borne out in the literature. For example, to flatten the hierarchy, we aimed to ensure a high ratio of learners to faculty, which has previously been described as important when building equitable learning environments [39]. We also developed a diverse faculty, including a mixture of genders, specialties and professions, and we worked with experts such as doctors with refugee status. In the future, we would hope to invite some of the refugee doctor cohort, now working in the NHS, to become faculty for future course delivery, as a further method to enhance social connections within our co-creative group.

The education literature extols the benefits of co-creation in the development of curricula. However, as in our case, further clarity is needed on the most effective ways to amplify the voices of learners when faced with complex power dynamics. Our approach to co-creation allowed us to identify and mitigate some learning barriers. For example, we identified the contributory factors to lateness and lack of attendance and found solutions that worked better for both learners and faculty. It helped to work co-creatively to consider broader learner needs, beyond only educational needs, and to nurture the building of social connections.

Developing the curricula alongside the refugee doctor cohort through action research cycles revealed the challenge that the cohort was initially either unaware of their limitations or felt unable to express them. This was highlighted in the example of ECG interpretation skills being over-estimated. We aimed to create a supportive learning environment and reduce emotions, such as stress or fear, that hinder learning [40]. Regular check-ins, reflection and discussions allowed the cohort to increase self-awareness around personal learning needs and the researchers to better understand the cohort’s learning needs. Over time, with increased comfort and familiarity, we all gained insight.

While we perceive many benefits to co-creative process in simulation-based medical education, there are challenges. It took considerably more time to develop the programme than if the design team had developed learning outcomes based on the literature and expectation of learner needs. With such a heterogeneous group, a development process that encouraged discussion and reflection added more complexity to areas such as content focus and learning priorities. Finding effective methods of gathering opinions from all members of the co-creative team was crucial.

At times, complex power dynamics influenced our ability to achieve open communication. We found the refugee doctor cohort often remarked, both verbally and in written feedback, on their gratitude for the opportunity to attend the course and they were reluctant to be critical. Despite our best efforts to normalize reflective learning and to seek areas for improvement, there were cultural beliefs around respect and hierarchy that could not be completely overcome.

While the post-session discussions were valuable, additional learning could have come from designated group or individual meetings with members of the refugee doctor cohort. Audio-recording post-session discussions, in addition to researcher field notes, would have increased data input for the action research cycles. Our iterative changes may have had different outcomes if the refugee doctor cohort had been more involved in the analytical aspects of the action research cycles. Having more refugee doctors involved in the research group from the start and in the co-design of simulation scenarios would have likely amplified their voices in our group more effectively.

Our decision to use simulation-based education with the refugee doctor cohort was novel. Our study demonstrates how action research cycles can provide the structure for the co-creative process. Using the cycles on a large and small scale created a tangible way to ensure reciprocity between learners and the simulation team throughout the development. Action research cycles encouraged reflection on the efficiency of our strategy. It highlighted where simulation alone was insufficient and where pre-learning and group-based discussions should be added. Possibly, the heterogeneity of our learner group means that three cycles of iteration were insufficient test time in the design process. We continue to test and only small iterative changes have occurred in subsequent learner cohorts. This suggests our approach was an effective method of curriculum development for heterogeneous learners.

This study was small, with only 18 learners, and the curriculum that we developed was a short 6-day course. The refugee doctors were referred to the simulation programme by the charity and may not have been an accurate representation of the larger refugee doctor cohort. While the refugee doctors were from diverse locations, the study took part in a single centre. We acknowledge that it may have been difficult for the cohort to provide constructive feedback. While the feedback forms were anonymous, the cohort may nevertheless have been keen to please the faculty with their evaluations. Unsatisfactory aspects of the course, from the perspective of the refugee doctors, may remain invisible to the faculty. We hope that through building relationships with the learners over time, they will be comfortable in speaking more freely.

This study describes the first phase of our simulation curriculum. We plan to use our co-creative action research approach to develop further phases of simulation-based curricula to support refugee doctors on their complex journey to thriving at work within healthcare.

Our study on the role the simulation curriculum played in refugee doctors reclaiming their identities and their social integration into the healthcare workforce has recently been published [9].

Further work could focus on investigating the transferability of this approach for developing simulation curricula for other heterogeneous groups, for example, international medical or nursing graduates integrating into host countries throughout the world.

The development of novel simulation curricula for learners with unknown learning needs is challenging. Kern’s steps to curriculum development could not provide a solution. Our co-creative approach, using action research cycles of iterative development, was effective for macro-level curriculum development goals and applicable at the micro level by adding granularity to content development. Our methodological approach helped to clarify achievable priorities agreed upon by both the simulation team and the learners. This approach could be replicated by others involved in simulation development. Collaborative, reflective relationships built through social connections are powerful and played a key part in the production of a bespoke simulation curriculum for the complex and heterogeneous group of refugee doctors integrating into the medical workforce.

We would like to thank Nisreen Eltom and Stephen Middleton from the VAST team for their contribution to the scenario design and Elizabeth Carney, Forth Valley Hospital librarian. We would also like to thank the faculty and staff at SCSCHF and the Bridges doctor participants who were involved in the process. Many thanks to the Scottish Government and The Bridges Charity for ongoing funding of the programme.

None declared.

This work was supported by a grant from the Scottish Government.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

How would you rate the session today overall?

Excellent, good, adequate, poor to very poor

What is it you like best?

What should we improve?

How does today’s simulation compare to previous?

What future training do you want?