Simulation is crucial in healthcare education as it offers a secure environment for learners to consolidate knowledge, skill acquisition and understand human factors to translate this knowledge and skill to improve patient care [1]. Simulation is now a mandatory component of training [2], courses and examinations.

Our study aimed to explore the simulation scape in hospitals in the East of England with a view to ensuring the standardisation of equipment, faculty, and debriefing techniques to enable consistent learning experiences.

Hospitals in East of England were identified, and a questionnaire was sent to simulation leads to gather information. Non-responding hospitals were contacted via switchboard, and virtual meetings were scheduled with them to obtain information. Data was subsequently analysed and compared.

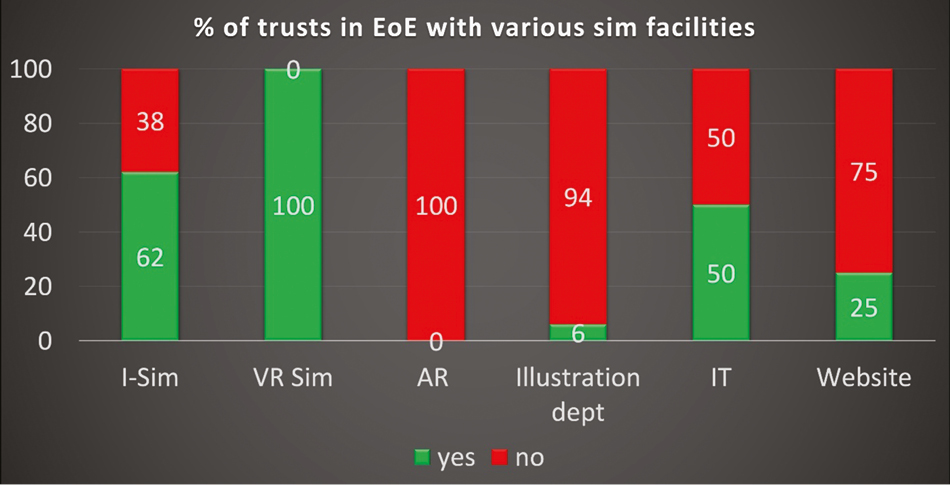

Eighty-nine percent of the trusts responded to the survey (16/18), and these hospitals were evenly spread across the region. The simulation facility varied (Figure 1-A87), with an average of three rooms being used for simulation and number of participants ranging from 8 to 90. 75% of hospitals had a debriefing room, 75% had a control room, 62% had adequate storage facilities, and 69% had custom-built simulation suites. Approximately 80% had a simulation manager, and 60% had a simulation technician and dedicated consultant. There was variability in mannikins; one trust had 15 low-fidelity mannequins, another had 7 high-fidelity mannequins, whilst some had zero. All trusts had VR simulation, no AR simulation and 62% had I-simulation. There was a variety of debriefing models used.

It can be inferred that the simulation-based learning experiences for participants in the East of England are inconsistent. This is due to variations in the debriefing models, equipment, fidelity, resources, and processes. Simplifying and standardising these processes is necessary, particularly ensuring consistency in debriefing, a crucial aspect of simulation-based education. Participant surveys would be useful to establish perceived qualitative differences in the learning experience.

Our study identified high costs, capacity constraints, and faculty-related issues. We recommended sharing our findings, exchanging ideas through a “Hub and Spoke” model, and holding an “Achievements in Sim” conference. We also suggested comparing data with other regions.

Authors confirm that all relevant ethical standards for research conduct and dissemination have been met. The submitting author confirms that relevant ethical approval was granted, if applicable.

1. Aggarwal R, Mytton OT, Derbrew M, Hananel D, Heydenburg M, Issenberg B, et al. Training and simulation for patient safety. Quality and Safety in Health Care [Internet]. 2010;19(suppl 2):i34–i43. Available from: https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/19/Suppl_2/i34.

2. Taught Programme Guidance for Foundation Doctors [Internet]. Available from: https://heeoe.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/taught_programme_for_foundation_doctors_20-21-_eoe_0.pdf.

We thank Mohammed Batcha for his valuable assistance in initiating this project.