There is growing evidence that instruction and guidance during simulation engagement can enhance explicit and subtle procedural knowledge and skills, medical knowledge, situation awareness and organization, and observation and reflection. However, instruction and guidance to scaffold learners during simulation engagement receive limited attention in published peer-reviewed literature, simulation practice guidelines and instructional design practices. This scoping review aimed to identify specific instruction or guidance strategies used to scaffold learners during simulation engagement, who or what provided support and guidance, who received instruction or guidance, and for what reasons.

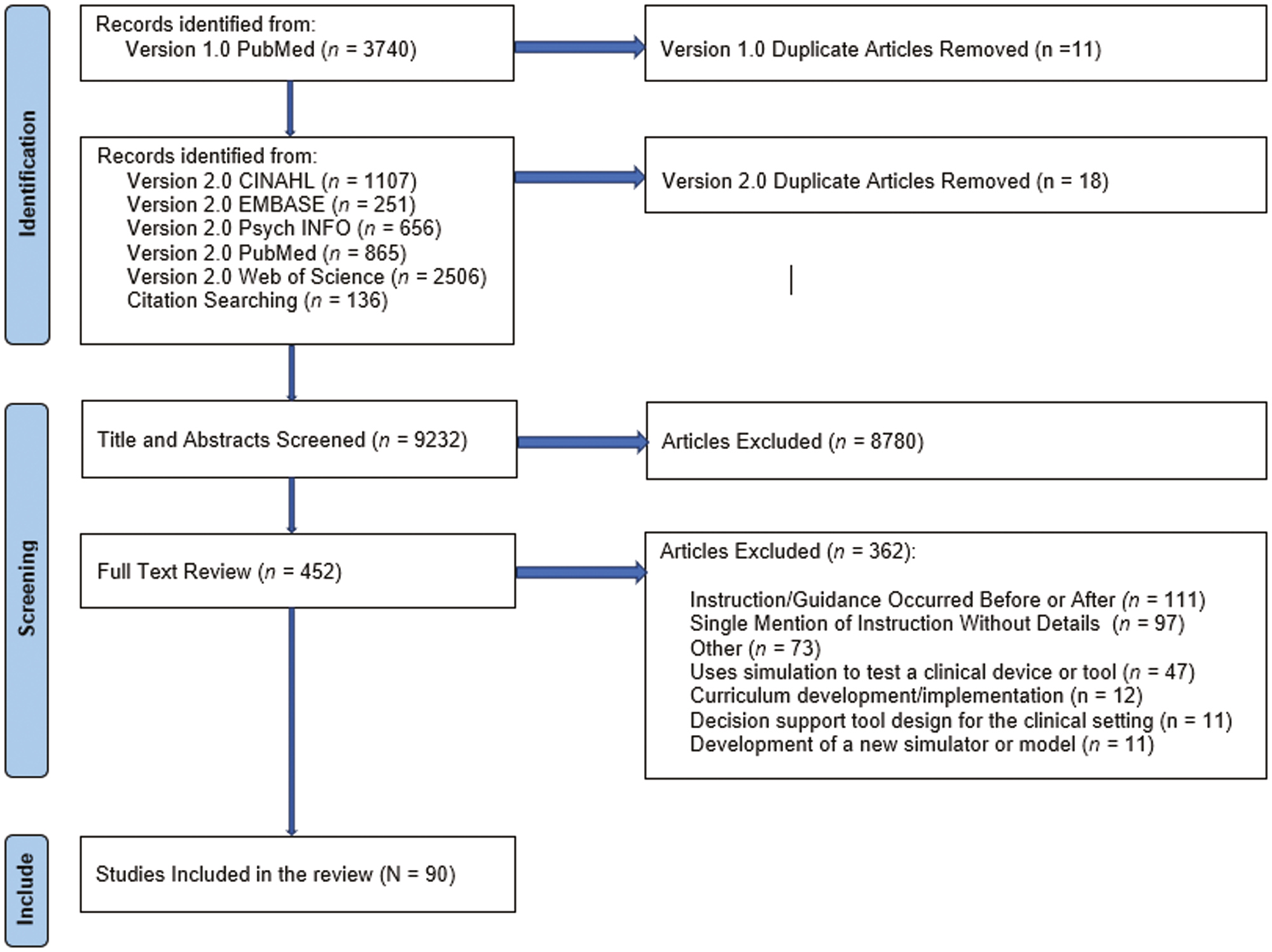

Guided by Reiser and Tabak’s perspectives on scaffolding, we conducted a scoping review following JBI Guidance. Included databases were PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO and Web of Science. No date boundary was set. All languages were eligible. Hand searching included six healthcare simulation journals, yielding 9232 articles at the start. Using Covidence, two reviewers independently screened all articles (title and abstract, full-text). Two independent reviewers extracted every third article. The content analysis enabled categorization and frequency counts.

Ninety articles were included. A human or computer tutor or a combination of human and computer tutors provides instruction and guidance. Strategies employed by human tutors were verbal guidance, checklists, collaboration scripts, encouragement, modelling, physical guidance and prescribed instructional strategies (e.g., rapid cycle deliberate practice). Strategies employed by computer tutors were audio prompts, visualization, modelling, step-by-step guides, intelligent tutoring systems and pause buttons. Most studies focused on pre-licensure and immediate post-graduate learners but continuing professional development learners were also represented. The most common reason for including instruction and guidance was to enhance learning without specific language regarding how or what aspects of learning were intended to be enhanced.

Although less prominent than pre- and post-simulation instructional strategies (e.g., pre-briefing, debriefing), there is a growing body of literature describing instruction and guidance for scaffolding learners during simulation engagements. Implications for practice, professional guidelines and terminology are discussed.

What this study adds:

•Despite receiving less attention than pre- and post-simulation instructional strategies such as pre-briefing and debriefing, descriptions of instruction and guidance provided during simulation engagement are increasingly common.

•There is a need to distinguish between facilitating simulations for implementation fidelity (i.e., ensuring the simulations unfold as planned) and providing instruction and guidance for the purpose of scaffolding learning.

•Instruction and guidance can be provided by human tutors, including more knowledgeable others (experienced professionals), near peers (those with slight differences in experience), peers (those with the same level of experience) and computer tutors.

•The findings of this scoping review provide a starting place for healthcare simulationists to consider when designing simulation-based learning activities. Human tutor strategies included verbal guidance, checklists, collaboration scripts, encouragement, modelling, physical guidance and prescribed instructional strategies (e.g., rapid cycle deliberate practice). Computer tutor strategies included audio prompts, visualization, modelling, step-by-step guides, intelligent tutoring systems and pause buttons.

•The authors of the included articles expressed diverse reasons for including instruction and guidance during simulation engagement, including enhancing learning, economic benefits, learners’ sensemaking, investigation and problem-solving processes, reflection, and articulation.

A critical review by McGaghie et al. [1] examining simulation-based medical education spanning 35 years (1969–2009) identified 12 features and best practices of simulation-based medical education: feedback, deliberate practice, curricular integration, outcome measurement, simulation fidelity, skill acquisition/maintenance, mastery learning, transfer to practice, team training, high-stakes testing, instructor training, and educational and professional content. However, McGaghie et al. [1] concluded that ‘the role of the instructor in facilitating, guiding, and motivating learners is shrouded in mystery’ (p. 59). They further argued that ‘effective simulation-based medical education is not easy or intuitive; clinical experience alone is not a proxy for simulation instructor effectiveness’ [1] (p. 59). More recently, Piquette et al. [2] examined the impact of supervision during acute care scenarios and concluded that ‘supervision of the learning opportunities created for trainees has not been insufficiently explored’ (p. 827).

Although McGaghie et al. [1] and Piquette et al. [2] indicate that instructional practices are shrouded in mystery, some instruction and guidance strategies, such as pre-briefing and debriefing, have garnered significant attention. For example, articles focusing on debriefing, a form of instruction and guidance after simulation engagement, are ubiquitous. Debriefing, defined as a guided conversation to explore and understand the relationships between events, actions, thoughts and feelings [3], is viewed as a critical instructional practice that promotes learning [4]. Debriefing is viewed as so essential that practice standards are reified in the International Nursing Association Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL) Standards of Best Practice [5] and by the prevalence of numerous instructor training workshops and courses.

Pre-briefing, sometimes called briefing, has also gained marked visibility and adoption. Like debriefing, pre-briefing is codified in the INACSL Standards of Best Practice and is intended to promote psychological safety by establishing a shared mental model and preparing learners for the simulation-based experience by orienting them with specific behavioural and performance expectations [6, 7]. Pre-briefing can also play a role in enhancing learning when combined with lectures, readings, and demonstrations [7–9]. Additionally, when learners have time to plan and set individual-level goals after receiving their pre-brief, learning is enhanced by enabling learners’ goal-setting, planning and motivation [7].

Conversely, instruction and guidance provided during simulation engagement have not garnered similar attention when compared to pre-briefing and debriefing. For example, in the SSH Dictionary [10], the terms ‘instructor’ and ‘instruction’ are used 15 times each, but only as part of other terms’ operational definitions (e.g., Feedback, Physical Exam Teaching Associate) [10]. For instance, ‘Feedback can be delivered by an instructor, a machine, a computer, a patient (or a simulated participant), or by other learners as long as it is part of the learning process’ [10] (p. 18). Under Physical Exam Teaching Associate, instruction involves ‘An individual who is trained to teach and provide feedback on basic physical exam techniques and process; serves as a coach and as a model (as the instructor and patient)’ [10] (p. 18). Notably, in each definition that includes the terms instructor or instruction, the act of teaching and enhancing learning is prioritized.

Supporting learners during simulation engagement is often referred to as facilitation, defined as ‘the structure and process to guide participants to work cohesively, to comprehend learning objectives and develop a plan to achieve desired outcomes’ [11] (p. 22). According to the INACSL Standards of Best Practice for Facilitation [11], Criteria 4, facilitation is ‘aimed to assist participants in achieving expected outcomes’ (p. 24). Assistance involves providing cues (predetermined or unplanned), prompts, or triggers when the simulations’ reality is unclear, refocusing learners when off track, or providing diagnostic findings such as laboratory or radiology results [11]. Furthermore, the healthcare simulation dictionary (Eds. 2.1) defines a facilitator as ‘an individual who is involved in the implementation and/or delivery of simulation activities or helps to bring about an outcome by providing indirect or unobtrusive assistance, guidance, or supervision’ [10] (p. 18). Although facilitation activities have a role in enhancing learning, thematically, they prioritize ensuring simulation implementation fidelity, defined as the degree to which an intervention is delivered as intended [12].

Recent research has shed light on the importance of instruction and guidance during simulation engagement. These studies demonstrate that when such support is provided, it can enhance the development of explicit and subtle procedural knowledge skills [13, 14]; diagnostic competence [15, 16] and observational skills [14]. For instance, Cauraugh et al. [13] found that when students received expert cognitive modelling and auditory elaboration during simulation practice, learners’ time to complete surgical procedures was reduced, and they made more purposeful instrument movements. In a grounded theory study published in 2012, Corey-Parker et al. [17] described how educators empowered students through adaptive scaffolding, involving observation, providing support when students struggle, and fading support when students can act independently. Furthermore, in a study published in 2018, MacKenzie et al. [14] explored co-construction using faculty who acted as a guide on the side. In this study, observation of peers with a guide on the side improved learners’ observation, feedback and clinical skills [14].

Two recent meta-analyses by Chernovika et al. [15, 16] examined the contribution of scaffolding, defined as ‘support during working on a task connected with a temporary shift of control over the learning process from a learner to a teacher or learning environment’ [16] (p. 3) to learning in problem-based and simulated contexts. Chernovika [15] found that strategies such as ‘assigning roles (g = .48), providing prompts (g = .47), and reflection phases (g = .58) have clear positive effects on diagnostic competencies’ (p. 183). In their subsequent meta-analysis, Chernovika [16] found that novice learners benefited the most from higher levels of support. In contrast, experienced learners benefited most when scaffolding strategies enabled them to rely on their existing self-regulatory skills [16].

Although these reviews indicate that providing scaffolding during simulation engagement enhances learning, several gaps remain. For example, both reviews [15, 16] included multiple professional domains, such as engineering, teacher education and healthcare. Furthermore, most healthcare-oriented articles addressed physician training, whereas the broader practice of healthcare simulation includes diverse health professionals. Moreover, Chernovika et al. relied on limited terminology to identify scaffolding, including simulation, competence, skill and teaching. Chernovika et al.’s use of PsychInfo, PsychArticles, ERIC and Medline excluded common databases common to health professions education, such as CINAHL and PubMed.

Reflecting on our practices and experiences with simulation-based learning activities (ZB and AB, authors), we acknowledged that we had employed instruction and guidance during simulation engagement to help learners when they struggled, appeared frustrated or needed a temporary bridge to get them through a challenging moment. Given the findings of our literature review and our own experiences, we conducted a scoping review that addressed several of the gaps we identified in our literature review, including

1.prioritizing healthcare simulation,

2.including the diverse health professions,

3.prioritizing studies emphasizing teaching and learning rather than facilitation for implementation fidelity, and

4.accounting for diverse terminology.

This scoping review, focusing on healthcare simulation, aimed to identify specific instruction or guidance strategies used during simulation engagement, who or what provided support and guidance, who received instruction or guidance, and for what reasons.

We selected Reiser and Tabak’s [18] perspectives on scaffolding, which draw on numerous socio-cultural traditions, including Wood, Bruner and Ross’ perspectives [19] on scaffolding during problem-solving, Vygotsky’s [20] zone of proximal development, and Rogoff’s [21] perspectives on guidance and support. Wood et al. [19] proposed the term scaffolding while studying children’s problem-solving processes. They found that when learners were supported by a more knowledgeable other (MKO), they could solve more complex problems than when alone. Scaffolding involves the joint participation of the learner and MKO assuming that the learner already has the knowledge and skills needed to complete the activity [18]. As the engagement progresses, MKOs use various strategies, such as verbal or written prompts, to help the learner when they struggle. When learners can complete the task independently, MKOs fade support until it is needed again.

One way to envision how scaffolding supports learning is to consider Reiser and Tabak’s [18] use of the metaphor of a bridge. This metaphor highlights how, when a learner is unaware of what strategies to use, is unable to execute a task well, or where they lack a robust conception of the problem, a more knowledgeable other step in, shares the workload with the learner, easing their struggles just enough to allow them to complete the task (i.e., cross the bridge). Scaffolding goals may include simplifying or restructuring tasks, so they are within reach of the learner, offsetting frustration to maintain interest, focusing the learner’s attention, and prompting learners to explain or reflect [18] (pp. 48–50).

Let’s consider a scenario-based simulation designed to teach the Enhanced Focused Assessment for Trauma (EFAST). In this scenario, a learner encountered difficulties orienting the ultrasound probe and applying sufficient pressure to obtain a quality pericardial view. Recognizing this, a more knowledgeable ultrasound Fellow stepped in to assist. The Fellow and the learner then jointly held the ultrasound probe, with the Fellow’s hand over the learner’s hand, guiding the prob to obtain the pericardial view. The Fellow also aided the learner in interpreting the image using verbal prompts, which involved structured questions and additional advice. Once completed, the Fellow stepped back, allowing the learner to retain autonomy and independence.

This example illustrates several vital principles of Reiser and Tabak’s [18] scaffolding approach. When sharing the scanning workload, the Fellow helps the novice learner engage with a real problem despite their lack of experience. The Fellow also restructures the task using verbal prompts to guide the learner’s interpretation of the ultrasound image. This restructuring also enables access to the Fellow’s mature scanning, interpretation and practice strategies during joint participation.

Although there are several advantages to scaffolding learners in complex learning environments like simulation, it is also essential to consider when scaffolding may be less effective or when it should be faded. For example, scaffolding efforts that prioritize outcomes or ‘getting the right answer’ without addressing the underlying process of the activity or procedure (e.g., EFAST), scaffolding will not help learners develop the process knowledge and skills they will need in future clinical encounters [18]. Moreover, there is also the risk of hypermediation – that is, providing too much support, or hypomediation, which may involve inaccurate assessments of a learner’s abilities, leading to insufficient support [18]. For example, using the example above, had the fellow not relinquished control of the ultrasound probe back to the learner, the learner would miss out on the important opportunity to apply what they had learned.

The goals of this review were best explored using a scoping review following Peters et al. [22] and the resources provided by the JBI [23, 24]. Specific reasons for a scoping review included identifying and mapping (a) instruction and guidance strategies employed during simulation engagement, (b) who or what provides support, and (c) why instruction or guidance was provided. Additionally, our background research showed diverse terminology and inconsistencies in definitions, behaviours, and characteristics; thus, an iterative approach of searching, screening, and extraction helped us account for variations in language. The review questions were:

1.What strategies are used to provide instruction or guidance to learners during simulation engagement?

2.Who or what is described as providing instruction or guidance while learners partake in a simulation-based learning event?

3.Why is instruction or guidance provided?

Collaborating with a librarian, we conducted two iterative searches of the literature, starting with terminology from our original literature review (Appendix A). No date boundary was set, and all languages were eligible. The first search – version 1.0 – was conducted in June of 2021 using PubMed and yielded 3737 articles. We then screened a random sample of 100 articles to locate additional terms and phrases we may have inadvertently excluded (e.g., our literature review focused mainly on human instructors). From this effort, we identified an additional five terms (Appendix A). We conducted a second search with the new terms and additional databases on 5 October 2022, yielding an additional 5380 articles – version 2.0. Databases included CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed and Web of Science. We also hand-searched six journals focusing on healthcare simulation: Advances in Simulation, BMJ STEL, Clinical Simulation in Nursing, International Journal of Healthcare Simulation, Simulation and Gaming, and Simulation in Healthcare, and the two previous reviews conducted by Chernovika et al. [15, 16]. After removing 29 duplications from the combined searches, 9232 articles remained for title and abstract screening (Figure 1 Prisma Diagram). Covidence was used for title and abstract and full-text screening and extraction.

Prisma diagram.

Before screening, additional reviewers were recruited and trained (DN, AK, MK, CR, LC), where they were introduced to the study, the concepts of scaffolding, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the software platform Covidence. Training sessions were recorded for later access as needed. All titles and abstracts were then independently screened by two reviewers (ZB, AB, DN, AK, MK, CR, LN). Inclusion and exclusion criteria for title and abstract screening are included in Appendix B. Conflicts were resolved via discussion during bi-weekly research meetings by the lead authors (AB, ZB). The title and abstract screening yielded 452 articles for full-text review (Figure 1).

Full-text review was completed by two reviewers (ZB, AB) who independently reviewed each article (n = 440). Articles with insufficient descriptions of guidance or support or that did not focus on guidance or support for the purpose of learning were excluded (Appendix C). Conflicts were resolved via discussion during bi-weekly meetings (AB, ZB) – full-text review yielded 90 articles for extraction (Figure 1).

As Pollock et al. [23] outlined, ZB and AB utilized an inductive approach during extraction. We also drew on our theoretical framework, scaffolding and guidance from other research team members (DN, AK, SG and MK). The extraction tool was tested with ten randomly selected articles using Covidence. After testing, ZB and AB met to discuss their experiences and refine the tool. We tested the extraction process again using the same procedure. After the second round of testing, we agreed on the extraction tool (Supplementary Material 1), containing three sub-sections: article demographics (e.g., first author, title, year published, learning topic), kinds of instruction or guidance provided (e.g., terminologies, operational definitions) and reasons for including instruction or guidance (e.g., study purpose statement and the ideas, observations, concepts, and prior knowledge that form the basis for a study [25], and the theoretical framework).

We (ZB, AB) then independently extracted all the remaining articles using Covidence. Every third article was independently extracted, and all extraction texts were reviewed by a second reviewer (ZB or AB). Articles that required more discussion or when there were disagreements in extraction were recorded in a shared Google Document and then discussed until a consensus was reached (ZB, AB). Consistent with scoping review guidelines, we did not critically appraise included articles [23].

The analysis involved several steps. First, the final data set was exported from Covidence to Microsoft Excel and aggregated and calculated frequency and percentages for article demographics. Then, given the significant heterogeneity in the terminology describing instruction and guidance, we used content analysis, ‘a research technique for making systematic, credible, or valid and replicable inferences from texts’ [26] (p. 7). To operationalize content analysis, we reviewed and coded the extracted text, often relying on Reiser and Tabak’s [18] perspectives to focus on coding our efforts regarding scaffolding. We then grouped like codes and calculated frequency counts and percentages [27].

The lead authors (ZB and AB) met regularly to discuss the codes, operational definitions, and analysis efforts and also shared interim findings with the fuller research team for additional feedback and guidance (DN, AK, SG, MK, LN). Furthermore, all researchers recorded analytic memos, recording their thoughts, ideas and decision-making.

Included article journals, study locations and topics were diverse, reflecting the numerous professions that research and employ healthcare simulation (Table 1). Most were published in healthcare simulation journals (n = 23, 25.6%). However, articles were also published in medical education journals (n = 19, 21.1%), numerous medical speciality journals (n = 18, 20.0%), nursing and nursing education (n = 8, 8.9%) and surgically oriented journals (n = 8, 8.9%). Fields such as computers, computer learning, artificial intelligence (n = 3, 3.3%), and healthcare and health informatics (n = 3, 3.3%) were also represented. Most studies were conducted in the United States (n = 36, 40.0%), Canada (n = 9, 10.0%) and Denmark (n = 8, 8.9%) (Table 1).

| Demographic category | Frequency (N = 90) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Journal focus | ||

| Simulation | 23 | 25.6% |

| Medical education | 19 | 21.1% |

| Medical specialty* | 18 | 20.0% |

| Nursing and nursing education | 8 | 8.9% |

| Surgery and surgical education | 8 | 8.9% |

| Computers, computer learning, artificial intelligence | 3 | 3.3% |

| Health information systems and informatics | 3 | 3.3% |

| Biomedical engineering | 2 | 2.2% |

| Pharmacy and pharmacology | 2 | 2.2% |

| Resuscitation | 2 | 2.2% |

| Country | ||

| United States | 36 | 40.0% |

| Other** | 10 | 11.1% |

| Canada | 9 | 10.0% |

| Denmark | 8 | 8.9% |

| Germany | 7 | 7.8% |

| Australia | 6 | 6.7% |

| United Kingdom | 3 | 3.3% |

| Japan | 3 | 3.3% |

| Finland | 2 | 2.2% |

| The Netherlands | 2 | 2.2% |

| Israel | 2 | 2.2% |

| Norway | 2 | 2.2% |

| Year article published | ||

| Prior to 2000 | 2 | 2.2% |

| 2000–2005 | 2 | 2.2% |

| 2006–2010 | 3 | 3.3% |

| 2011–2015 | 20 | 22.2% |

| 2016–2020 | 42 | 46.7% |

| 2021–2022 (October) | 21 | 23.3% |

| Learner types | ||

| Undergraduate learners | ||

| Medical students | 28 | 31.1% |

| Nursing students | 13 | 14.4% |

| Other students*** | 4 | 4.4% |

| Graduate learners | ||

| Residents | 15 | 16.7% |

| Graduate nursing | 2 | 2.2% |

| Combined | 14 | 15.6% |

| Continuing professionals | 11 | 12.2% |

| Other | 3 | 3.33% |

| Learning topic | ||

| Resuscitation | 28 | 31.1% |

| Procedural skills (non-surgical) | 16 | 17.8% |

| Surgical procedures or skills | 13 | 14.4% |

| Assessment | 13 | 14.4% |

| Ultrasound | 6 | 7.8% |

| Other | 6 | 7.8% |

| Patient safety | 4 | 4.4% |

| Communication | 4 | 4.4% |

| Simulation genre | ||

| Scenario-based | 44 | 48.9 |

| Procedural-based | 43 | 47.8% |

| Both | 3 | 3.3% |

Notes: Bolding indicates the highest frequency count.

*Medical speciality journals included aeromedicine, anaesthesia, clinical medicine, dental education, emergency medicine, gastroenterology, obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics, physiotherapy, otology, radiology, rhinology, social work and ultrasound.

**Other countries included Thailand, Switzerland, Denmark, Italy, Taiwan, India, Brazil, Rwanda, Korea and Sweden.

***Other students included dental, pharmacy, social work and undescribed participants. Scenario-based simulations are guided by a narrative and incorporate many complexities associated with clinical practice, such as assuming a designated role (e.g., primary nurse, attending), engaging with a patient or support person and interacting with other healthcare professionals [28]. Procedural-based simulations are simulations that represent a partial system and are used to emphasize the teaching and practice of a designated skill [28].

Most articles were published after 2016 (n = 62, 68.9%). Most learners were undergraduate medical (n = 28, 31.1%) or nursing students (n = 13, 14.4%), followed by graduate medical (n = 15, 16.7%) and graduate nursing students (n = 2, 2.2%). Fourteen articles (15.6%) described combinations of learners of different levels. Learners in 11 articles (12.2%) were continuing professionals. The most common topics were resuscitation (n = 28, 31%), non-surgical procedural skills (n = 16, 18%), surgical procedures or skills (n = 13, 14%), and patient assessment (n = 13, 14%). The simulation genre was nearly equal; among 90 included studies, 48.9% (n = 44) focused on scenario-based simulations, and 47.8% (n = 43) focused on procedural skills (i.e., learning to complete a technical skill [10]). Three articles described a combination of scenario and procedurally based simulations (n = 3, 3.3%).

Diverse instruction and guidance strategies were described and varied based on who or what provided support. Human tutor strategies included verbal guidance (n = 35) [17, 29, 31–33, 35–48, 50–54, 57–61, 78, 79, 119, 121–123], predetermined instructional strategies (n = 17) [30, 34, 62–76], modelling (n = 10) [32, 46, 50, 54, 57, 61, 77–80], checklists (n = 3) [49, 81, 82], collaboration scripts (n = 2) [83, 84] and encouragement (n = 1) [59] (Table 2). Computer tutor strategies were audio prompts (n = 16) [34, 39, 58, 85–92, 94–97, 126], visualization (n = 11) [55, 60, 85, 90, 91, 95, 98–102], step-by-step guides (n = 8) [30, 31, 49, 76, 98, 99, 103, 104], modelling (n = 6) [45, 56, 105–107], intelligent tutoring systems (n = 3) [108–110] and pause buttons (n = 2) [93, 111].

| Strategy | Operational definition | Included article references |

|---|---|---|

| Human Tutor Strategies | ||

| Verbal guidance (n = 35) | Verbal guidance refers to using spoken language to convey information, instructions, explanations and feedback to learners. Verbal guidance can take various forms, including instruction or prompts used to help learners advance when struggling [112]. | [17, 29, 31–33, 35–48, 50–54, 57–61, 78, 79, 119, 121–123] |

| Predetermined instructional strategy (n = 17) | Instructional strategies were predetermined instruction and guidance approaches that comprised various individual instructional strategies. Examples include Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice and the Peyton Four Step approach for teaching procedural skills. | [30, 34, 62–76] |

| Modelling (n = 10) | Refers to the instructional strategy where the teacher demonstrates a concept, skill or behaviour for students, providing them with a clear example to follow. Modelling often includes verbalization of the steps and processes to make thought processes visible to the learner. This approach helps students understand what is expected of them, provides a visual or concrete representation of the learning objective, and can promote a sense of personal efficacy [113, 114]. | [32, 46, 50, 54, 57, 61, 77–80] |

| Checklist (n = 3) | Tools that set out specific criteria or steps to be taken. They assist educators and students in determining which steps to take or were taken to gauge skill development or progress. | [49, 81, 82] |

| Collaboration script (n = 2) | Refers to a set of guidelines or instructions that structure and guide interactions among learners during collaborative activities (e.g., a simulated encounter). These scripts are designed to enhance the effectiveness of collaborative learning experiences by providing a framework for communication, coordination and cooperation among group members [115]. | [83, 84] |

| Encouragement (n = 1) | The deliberate effort by educators to inspire, motivate, and support students in their learning process. It involves fostering a positive and supportive learning environment that empowers students to take risks, overcome challenges and achieve their academic and personal goals. Encouragement can take various forms, such as positive feedback, praise and providing opportunities for growth [113]. | [59] |

| Metacognitive prompts (n = 1) | Metacognitive prompts refer to cues or questions designed to encourage individuals to reflect on their own actions. These prompts aim to enhance metacognition, which involves awareness and understanding of one’s own thought processes, knowledge and cognitive abilities [116]. | [59] |

| Physical guidance (n = 1) | This type of guidance involves direct manipulation or physical interaction to help students grasp concepts or perform tasks [112]. | [53] |

| Computer tutor strategies | ||

| Audio prompts (n = 16) | Audio prompts are external resources or support that provide learners with select process knowledge, such as which steps to take next. | [34, 39, 58, 85–92, 94–97, 126] |

| Visualization (n = 11) | Visualization refers to the use of graphical or spatial representations of information to aid the understanding and retention of concepts. The goal is to make complex information more accessible and comprehensible, facilitating a deeper understanding of the subject matter. | [55, 60, 85, 90, 91, 95, 98–102] |

| Step-by-step guide (n = 8) | Step-by-step guides provided learners with detailed instructions to offload some aspects of a task (e.g., recalling procedural steps) but not others (e.g., motor tasks). | [30, 31, 49, 76, 98, 99, 103, 104] |

| Modelling (video) (n = 6) | Like human tutors’ modelling, computer tutor modelling refers to demonstrations of a concept, skill, or behaviour for learners. However, computer tutor modelling was delivered via pre-recorded videos [113, 114]. | [45, 56, 98, 105–107] |

| Intelligent tutoring system (n = 3) | Intelligent Tutoring Systems, commonly known as ITSs, are computer programs designed to deliver individualized instruction and feedback to learners. These systems harness AI techniques to offer a learning environment that adapts to the student’s needs, creating a one-on-one educational experience [117]. | [108–110] |

| Pause button (n = 2) | A temporary stop to action. Pauses were incorporated to enable learners to decrease frustration and cognitive load and access other instructional supports. | [93, 111] |

Of the included articles (N = 90), instruction and guidance during simulation engagement were provided by human tutors (n = 50, 55.56%), computer tutors (n = 28, 31.11%), or a combination of human and computer tutors (n = 12, 13.33%) (Table 3). Among human-tutor instances, almost half described a single support strategy (n = 24, 48.00%), and the remaining articles described multiple strategies (n = 24, 48.00%). Two articles described the presence of a human tutor (n = 2, 4.200%), but we could not determine the number of strategies used.

| Role | Operational definition | Guidance and support strategies used | Included article citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human tutors (n = 50) | |||

| More Knowledgeable Other (n = 31) | Instances where individuals with a greater understanding or a higher ability level than the learner regarding a specific task, concept, or process [19, 20]. | Verbal Guidance, Pre-determined Instructional Strategy, Modelling, Physical Guidance, and Encouragement | [29, 32, 33, 35–38, 43, 44, 46, 50–53, 57, 59, 62–74, 118, 119] |

| Peers (n = 9) | Learners who taught one or more learners of a similar ability [120]. | Verbal Guidance, Modelling, Checklists, Collaboration Scripts | [78, 80–84, 121–123] |

| Combined MKO and Peer (n = 7) | Instances that described guidance and support provided by MKOs and peers. | Verbal Guidance, Modelling | [17, 40–42, 48, 54, 61] |

| Near-Peer (n = 2) | Instances where learners who are one or more years senior to another learner provided support [124, 125]. | Verbal Guidance, Modelling | [77, 79] |

| Not Specified (n = 1) | Instances where a human tutor provided guidance or support, but there was insufficient description to determine their role. | Pre-determined Instructional Strategy | [75] |

| Computer tutors (n = 28) | Instances where a computer-based system or program is designed to assist and enhance the learning process. | Prompts, Visualization, Step-by-Step Guide, Modelling, Intelligent Tutoring System, and Pause buttons | [85–111, 126] |

| Combination of human tutors and computer tutors (n = 12) | Instances where human and computer tutors were included. | Verbal Guidance, Checklist, Audio Prompts, Interactive Whiteboard, Modelling, Pneumonic, Predetermined Instructional Strategy, Visualization, | [30, 31, 34, 39, 45, 47, 49, 55, 56, 58, 60, 76] |

Notes: Bolding indicates the top two strategies employed by each specific group. Italics indicates a type of human tutor.

Most human tutors were more knowledgeable others (MKO) (n = 31, 62.00%) [29, 32, 33, 35–38, 43, 44, 46, 50–53, 57, 59, 62–74, 118, 119], followed by peers (n = 9, 18.00%) [78, 80–84, 121–123], combined MKOs and peers (n = 7, 14.00%) [17, 40–42, 48, 54, 61], and near peers (n = 2, 4.00%) [77, 79]. One article did not specify who provided guidance and support (n = 1, 2.00%) (75).

MKOs were individuals with a greater understanding or ability level than the learner regarding a specific task, concept, or process [19, 20]. MKOs employed diverse strategies, including verbal guidance (n = 17) [29, 32, 33, 35–38, 43, 44, 46, 50–53, 57, 59, 119], predetermined instructional strategies (e.g., rapid-cycle deliberate practice, Peyton’s Four-Step Strategy) (n = 13) [62–74], modelling (n = 4) [32, 46, 50, 57], metacognitive prompts (n = 1) [118], physical guidance (n = 1) [53], and encouragement (n = 1) [59].

Eleven articles described peer tutors (i.e., instances where learners taught one or more fellow learners of similar ability) [120]. When peers instructed or guided each other, they used verbal guidance most frequently (n = 4) [78, 121–123], followed by modelling (i.e., demonstrations) (n = 2) [78, 123], checklists (n = 2) [81, 82], and collaboration scripts (n = 2) [83, 84] (Table 3). Compared to the strategies used by MKOs, peers used fewer complex strategies; for example, no peers used prescribed instructional strategies. Additionally, instances in which peers used checklists and collaboration scripts suggest that given their novice status, they, too, needed support to guide their peers.

Seven articles described a combination of MKOs and peer tutors [17, 40–42, 48, 54, 61]. Strategies used by MKOs, and peers included verbal guidance (n = 7) [17, 40–42, 48, 54, 61] modelling (n = 2) [54, 61].

Two articles described near-peer instruction and guidance, defined as instances in which learners who were one or more years senior to another learner provided support) [124, 125]. Near Peers relied primarily on modelling (n = 2) [77, 79] and verbal guidance (n = 1) [79].

Computer tutors comprised nearly one-third (n = 28, 31.11%) of the included articles. Computer tutors involved in computer-based systems or programmes designed to assist and enhance learning. Sometimes, computer tutors used algorithms and artificial intelligence to provide personalized and adaptive support. Most articles described using a single instructional or guidance strategy (n = 22, 79%) [85–90, 92–94, 96, 97, 100–104, 106–110, 126]. The remainder described using two or more computer-tutor strategies (n = 6, 21%) [91, 95, 98, 99, 105, 111].

Audio prompts were the most common computer-tutor strategy employed (n = 13) [85–92, 94–97, 126] followed by visualization (n = 9) [85, 90, 91, 95, 98–102], step-by-step guides (n = 4) [98, 99, 103, 104], modelling via recorded videos (n = 4) [98, 105–107], intelligent tutoring systems (n = 3) [108–110] and pause buttons (n = 2) [93, 111].

Audio prompts provided learners with select process knowledge, such as which steps to take, or how hard or fast to compress. Ten articles using audio prompts focused on resuscitation skills [85–87, 90–92, 94, 96, 97, 126]. The most common prompts described were audible noises, such as beeps, projected from a device to help learners focus their attention on achieving the correct actions (e.g., compression rate). Sometimes, audio prompts included brief phrases such as ‘push harder’ or ‘push faster’ and were provided when the device analysed the learner’s performance. Devices that provided auditory prompts included metronomes, QCPR with SkillReporter, or programmes built into medical devices (e.g., defibrillator).

Nine articles described the use of visualization (n = 9) [85, 90, 91, 95, 98–102]. Learning topics employing visualization were surgical skills such as skin suturing [95] and mastoidectomy [98, 99, 103], and ultrasound scanning or ultrasound-guided procedures [100-102]. Visualization included visual guides projected onto the designated anatomy [95, 100, 102], or where colour was used to indicate where and how much volume to drill (e.g., green highlighting used in mastoidectomy training) [98, 99, 103]. Wilson et al. [102] included pointers or arrows to help enhance spatial orientation during ultrasound-guided procedures. Skinner et al. [101] used visualization to provide feedback to learners whereby image planes were superimposed over a three-dimensional reconstruction of the heart.

Four articles described modelling involving pre-recorded videos demonstrating MKOs performing a specific procedural skill [98, 105–107]. Learning topics included suturing [105, 106], mastoidectomy [98], and endotracheal intubation and lumbar puncture [107]. In all four studies, the authors expressed an economic advantage to using modelling videos, specifically that they could replace a more knowledgeable other. Three of the four articles indicated another advantage of using videos: their accessibility on demand [98, 105–107].

Four articles (n = 4) described step-by-step guides that provided learners with detailed instructions to offload some aspects of the task (e.g., recalling procedural steps) but not others (e.g., motor tasks) [98, 99, 103, 104]. For example, three studies employed text-based step-by-step guides projected on the computer screen during mastoidectomy training [98, 99, 103].

Three articles (n = 3) described using intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) to support learners’ efforts during simulation engagement [108–110]. ITSs are computer programs that possess knowledge of specific skills, monitor learners’ activities and progress, provide specific feedback in real-time, and adapt future problems to create a one-on-one educational experience [117]. For example, Eliot et al. [108] describe a computer-based simulator that monitored students’ interactions with a simulated patient experiencing cardiac arrest, provided dynamic feedback during treatment, and anticipated and suggested alternative expert solutions to the learner as the cases progressed. Similarly, Mariani et al. [109] employed an ITS to support students while they practised robot-assisted surgeries, and Rhienmora et al. [110] employed an ITS for crown preparation. Authors of these articles expressed that an ITS’s dynamic approach was more like a human tutor’s dynamic approach and that it could meet learners at their learning level.

Lastly, two studies employed pause buttons that let learners temporarily stop the simulation to decrease cognitive load [93] or promote metacognitive reflection [111]. For example, Lee et al. [93] integrated a pause button in emergency medicine scenarios, arguing that temporary pauses enable learners to take a moment to reorient during stressful moments by limiting the influx of new information and minimizing the negative impact of too much stress on working memory. Fink et al. [111] employed a pause button during diagnostic accuracy scenarios where pauses were intended to help induce reflective processes. Here, learners were given specific instructions and dedicated time to reflect on the initial diagnostic hypothesis, alternative diagnostic hypotheses, and reasons for and against their hypotheses [111].

Twelve articles described combinations of human and computer tutor arrangements. Six of 12 articles described the combination of verbal guidance paired with step-by-step guides [31], audio prompts [39, 58], modelling videos [45], an interactive whiteboard [47] and visualization [60]. Three studies described combinations of predetermined instructional strategies (i.e., RCDP) combined with step-by-step guides [30, 76] and audio prompts [34]. Two studies described the presence of human tutors but did not specify what strategies they used when combined with visualization [55] and modelling videos [56]. Mossenson et al. [49] described using checklists used by human tutors combined with computer-based step-by-step guides.

Reasons for including instruction and guidance were to enhance learning (generic) (n = 51), managing instruction and problem-solving processes (n = 26), sensemaking (n = 25), economic reasons (n = 23) (Table 4), and articulation and reflection (n = 10). Most articles expressed one rationale for including instruction and guidance (n = 54, 60.0%) [17, 29, 34–37, 40, 41, 43, 47–60, 63, 65–70, 72, 73, 75, 78–80, 82, 85, 89–94, 98, 100, 101, 103, 105, 107, 109, 111, 119, 126]. Of included articles expressing a single rationale for including instruction and guidance, most were enhanced learning (n = 42, 77.78%) [17, 29, 34–37, 40, 41, 43, 47, 48, 50, 51, 53–55, 57–60, 63, 65, 66, 68–70, 73, 75, 78, 80, 85, 90–94, 98, 100, 103, 111, 119, 126], followed by economics (n = 10, 18.52%) [49, 52, 56, 67, 72, 79, 101, 105, 107, 109], managing instruction and problem-solving processes (n = 1, 1.85%) [82]. One article did not express a rationale(n = 1, 1.85%) [89]. Among articles expressing multiple reasons for including instruction and guidance (n = 36, 40.00%) [30–33, 38, 39, 42, 44–46, 61, 62, 64, 71, 74, 76, 77, 81, 83, 84, 86–88, 95–97, 99, 102, 104, 106, 108, 110, 118, 121–123]. These included sensemaking (n = 25) [30, 32, 33, 38, 39, 42, 61, 62, 71, 74, 76, 81, 83, 84, 86–88, 95–97, 102, 106, 118, 122, 123], articulation and reflection (n = 10) [30, 64, 71, 74, 76, 77, 88, 95, 118, 122], managing instruction and problem-solving processes (n = 25) [30, 32, 33, 38, 39, 42, 61, 62, 71, 74, 76, 81, 83, 84, 86–88, 95–97, 102, 106, 118, 122, 123], enhanced learning (n = 9) [31, 42, 44–46, 99, 104, 108, 121], and economics (n = 13) [31, 32, 44–46, 76, 81, 86, 104, 106, 108, 110, 121]. Note that percentages were not calculated because some articles reported multiple strategies.

Articles that did not express a specific reason for including instruction and guidance but indicated a generic goal of enhancing learning were coded as enhanced learning and were the most common (n = 51) [17, 29, 31, 34–37, 40–48, 50, 51, 53–55, 57–60, 63, 65, 66, 68–70, 73, 75, 78, 80, 85, 90–94, 98–100, 103, 104, 108, 111, 119, 121, 126]. We used this code when the authors’ language was imprecise or heterogeneous, preventing more detailed coding.

Sensemaking and managing instruction and problem-solving processes were most commonly used together (n = 25) [30, 32, 33, 38, 39, 42, 61, 62, 71, 74, 76, 81, 83, 84, 86–88, 95–97, 102, 106, 118, 122, 123]. Sensemaking involved learners organizing new knowledge with assistance [18]. Managing instruction and problem-solving involved the use of supports to explore and generate answers to new questions and explore solutions to new problem sets. For instance, Tobase [97] looked at the utilization of technology supports in CPR to provide immediate feedback allowing learners to adjust their performance. This scaffold improved learners’ ability to assess CPR quality(sensemaking), evaluate the gap in performance (investigation), and try a new technique with immediate feedback (problem-solving). Another study by Wilson [102] examined the use of ultrasound (US) devices that provided real-time navigation that provided a visualization overlay compared to a traditional US display. By providing visualization support novice learners were more successful in needle guidance than traditional US (sensemaking), had improved accuracy, fewer redirections (investigation), and improved confidence in the procedure overall (problem-solving).

Economic reasons for including instruction and guidance were the least common rationale (n = 23) [31, 32, 44–46, 49, 52, 56, 63, 67, 72, 76, 79, 81, 101, 104–110, 121], meaning that there was a desire to improve learning and a recognition that active instruction and guidance could save time, money and resources or address low-volume situations. The most common economic reasons included articles expressing how learning was not only enhanced but required fewer faculty resources which allowed for more efficient use of limited simulation resources (n = 11) [31, 45, 49, 52, 79, 81, 101, 104–107]. Time was another common economic reason included and was split between allowing time for the learner to complete training and a need to provide instruction and guidance when MKO, such as faculty, were scarce. Another area less commonly described, but not anticipated was the use of instruction and guidance to improve areas of low-volume/high-risk procedural skills (n = 2) [67, 76].

| Category | Operational characteristics | Citation numbers |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced learning (Generic) (n = 51) |

Instructional focus - How to teach - How individuals learn best - How to design a scenario for learning - How does feedback impact learning Learner focus - What enables learning - Who enables learning - Why does learning happen |

17, 29, 31, 34–36, 38, 40–48, 50, 51, 53–55, 57–60, 63, 65, 66, 68–70, 73, 75, 78, 80, 85, 90–94, 98–100, 103, 104, 108, 111, 119, 121, 126 |

| Managing investigation and problem-solving processes (n = 26) | Providing assistance with making choices and supporting the proposed activities to reach the desired end state [18]. | 30, 32, 33, 37, 39, 42, 61, 62, 71, 74, 76, 81–84, 86–88, 95–97, 102, 106, 118, 122, 123 |

| Sensemaking (n = 25) | Making sense involves giving meaning to something, especially new developments and experiences [18]. | 30, 32, 33, 37, 39, 42, 61, 62, 71, 74, 76, 81, 83, 84, 86–88, 95–97, 102, 106, 118, 122, 123 |

| Economic (n = 23) | Resources - Focused on reducing instructor resources needed for learning. Time - Optimizing educational time to achieve results - Extending educational hours outside of regular hospital hours - Improving time to competency in a specific skill Low volume - High-risk, low-volume procedures essential for practice but often not encountered in regular training and utilize simulation to improve repetitions Low resource setting - Limited access to medication, equipment, supplies, and devices. - Less‐developed infrastructure (electrical power, transportation, controlled) - Limited access to trained educators |

31, 32, 44–46, 49, 52, 56, 67, 72, 76, 79, 81, 86, 101, 104–110, 121 |

| Articulation and reflection (n = 10) | Assisting with verbalization of thinking process and retrospectively looking at solutions to support learning [18]. | 30, 64, 71, 74, 76, 77, 88, 95, 118, 122 |

We identified 90 articles suggesting that providing instruction and guidance during simulation engagement is common and on the rise, with 63 (70%) articles published since 2016. This scoping review allowed us to peer into the black box of guidance and instruction, revealing that human and computer tutors used diverse instructional strategies to scaffold learning during healthcare simulation engagement. The findings therefore begin to rectify prior concerns raised by McGaghie et al. [1] when they indicated that ‘the role of the instructor in facilitating, guiding, and motivating learners is shrouded in mystery’ (p. 59).

The findings add specificity to Chernovika et al. [15], who argued that simulation-based learning activities are likely highly scaffolded learning environments. Specifically, both human and computer-based tutors can support learners during simulation engagement with the intent to promote learning rather than for simulation fidelity alone. Furthermore, the findings also indicate that the specific strategies used, such as modelling, verbal support and physical guidance, align with teaching and instruction behaviours. Thus, the findings also point to a clear distinction between facilitating simulations for implementation fidelity (i.e., ensuring the simulations unfold as planned) and providing instruction and guidance for the purpose of scaffolding learning.

This review also revealed several critical areas that warrant further attention regarding using instructional and guidance to scaffold learners. First, authors of included articles infrequently explained why they included instruction and guidance (i.e., 51 of 90 articles used the generalized argument of enhancing learning). Similarly, among authors that included combinations of supports (e.g., human and computer tutors), many did so without providing detailed rationales for combining strategies. These omissions reflect missed opportunities to elaborate on why, how and when to scaffold learners during healthcare simulation.

Along similar lines, the authors of included articles frequently used diverse terminology to describe scaffolding, but rarely referenced the scaffolding literature. This suggests that awareness of pedagogical strategies associated with scaffolding may also be limited. We encourage simulationists to consider research and theoretical perspectives regarding employing pedagogical strategies to scaffold learners, such as Wood et al. [19], Paradise and Rogoff [127], Reiser and Tabak [18], and Puntambekar [128]. For those exploring computer tutoring arrangements, readers may consider Azevedo and Hadwin [116] and Lajoie [129].

Equally important is knowing when to remove scaffolds to prevent hypermediation or what might lead instructors to inaccurately assess learners’ needs. Although some studies in our review explored how scaffolding strategies were added and later removed, such as Mariani et al. [109], Rienmora et al. [110], and Craft et al. [104], most articles did not. Prior research and theoretical goals of scaffolding argue that scaffolding should be tailored to the learner’s needs and follow a pattern of escalation followed by fading when there is evidence that learners can regulate their efforts. Theoretical and research articles by Wertsch et al. [130] and Puttambaker and Hubscher [128] may be helpful to simulationists.

We encountered several challenges while conducting this review, the most significant of which was the variability in language describing instruction and guidance and the frequency with which we encountered them. Specifically, we encountered new terms and phrases at all stages of the review which often created tension around what additional constructs should be included. Simultaneously, we had to balance these decisions with a need to set boundaries for this review while considering the inclusive nature of a scoping review alongside the age of the last database search. As a result, we may have missed some articles.

The included articles often had incomplete explanations of instruction and guidance and multiple undefined terminologies. To mitigate them, we conducted two rounds of searching, where the terminology in the second search reflected terminology identified during the first round of screening. Secondly, to address the imprecise and non-uniform language, we relied on the construct of scaffolding theory to guide our inclusion and exclusion decisions. Given that the included articles coalesced around similar themes (e.g., human and computer tutor strategies and rationales), we believe these findings provide a comprehensive foundation to advance future discussions regarding instruction and guidance. Different researchers may have selected different terminologies, constructs or groupings.

This review reveals diverse ways in which human and computer tutors scaffold learners while they engage in healthcare-oriented simulations and thus indicates that scaffolding is not limited to the pre - and post-simulation stages. As a result, we propose that simulationists should be viewed as a system whereby simulationists and designers can make strategic steps to promote learning before, during and after engagement. The findings also revealed several gaps regarding why, when and how to integrate scaffolding, knowledge surrounding pedagogical practices and publishing guidance. One potential solution may involve developing INACSL practice standards emphasizing human and computer tutors’ role in providing instruction and guidance during simulation engagement. Similarly, we suggest the inclusion of the terms human and computer tutors in the simulation dictionary to help align terminology and further clarify the distinction between facilitation for implementation fidelity and tutoring for instruction and guidance. We strongly encourage researchers and policy-makers to draw on the already extensive literature on scaffolding as a starting place (e.g., Reiser and Tabak [18], and Puntambekar [128]). Moreover, we encourage the editors of the leading simulation journals to consider ways to guide authors’ reporting practices regarding how and what should be included when describing a simulation intervention. For example, journals could include guidelines for authors to encourage consistent reporting about whether learners engaged independently or if they were scaffolded by a tutor. Doing so would help shed light on how common human and computer tutors are in practice, and also account for the role that tutoring may play in enhancing learning.

Looking ahead, our findings open up several avenues for future research and development. There is a need to further examine the distinctions between facilitation for fidelity and tutoring, especially among individuals engaging as embedded or simulated patients who may shift back and forth between the two activities. Given the diversity of terminology used in healthcare simulation to describe human and computer tutors and the age of the data set identified for this study, additional systematic reviews focusing more deeply on human and computer tutors in healthcare simulation are warranted. Additionally, while this review articulated that one of the ways to scaffold learning in simulations is through the use of human and computer tutors, there is a need to further understand what other components of simulation scaffold learners. Moreover, we need to determine how and when to scaffold learners’ efforts and when to fade those supports in simulated contexts. We believe that taking these next steps will play an essential role in advancing healthcare simulation.

Supplementary data are available at The Journal of Healthcare Simulation online.

We thank Rhonda Allard, MLIS, whose support and guidance during the search process were invaluable. We would also like to thank Mr. Joe Costello, MSIS, and Ms. Emily Scarlet, MS, for their support in formatting the manuscript, their advice regarding presenting and organizing the tables and figures, and reference insertion. This project would not have been possible without their contributions. We are also grateful for the time and effort the reviewers put into reviewing earlier versions of this manuscript. The manuscript is much improved because of your efforts.

ZB and AB took the lead on the original conception and design of this research. They were later joined by DN, AK, and SG, who furthered the conception and design. MK, LNC, and CR made significant contributions to analysis. All authors partook in drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version for submission and have agreed to be accountable for the work.

None declared.

Institutional review was not required for this study because the data were in the public domain.

The extracted data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

The views expressed in this presentation do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, the Henry M. Jackson Foundation, or the U.S. Government.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

95.

96.

97.

98.

99.

100.

101.

102.

103.

104.

105.

106.

107.

108.

109.

110.

111.

112.

113.

114.

115.

116.

117.

118.

119.

120.

121.

122.

123.

124.

125.

126.

127.

128.

129.

130.

Search Strategy v 1.0

| Database | Search parameters |

|---|---|

| Search Strategy (n=3,740) 3 Duplicates June, 2021 |

(“Medical simulation”[tiab] OR “nursing simulation”[tiab] OR “Simulation-based”[tiab] OR “Healthcare simulation”[tiab] OR “simulated patient”[tiab] OR “simulated patients”[tiab] OR “simulated person”[tiab] OR “simulated people”[tiab] OR “simulated participant”[tiab] OR “simulated participants”[tiab] OR “simulation patient”[tiab] OR “simulation patients”[tiab] OR “simulation person”[tiab] OR “simulation people”[tiab] OR “simulation participant”[tiab] OR “simulation participants”[tiab] OR telesimulation[tiab] OR “simulation educator”[tiab]) ((during[tiab] AND simulat*[tiab]) OR “within event”[tiab] OR “within-event”[tiab] OR “within-event learning”[tiab] OR “during simulation”[tiab] OR “during the simulation”[tiab] OR “during the clinical scenario”[tiab] OR “during the clinical simulation”[tiab] OR “during simulated patient”[tiab] OR “during the simulated scenario”[tiab] OR “Intra-simulation learning”[tiab] OR “intrasimulation”[tiab] OR (debrief*[tiab] AND during[tiab] AND simulation*[tiab]) OR “In-scenario instruction”[tiab]) (Facilitation[tiab] OR Facilitator[tiab] OR Support[tiab] OR Guidance[tiab] OR coaching[tiab] OR “deliberate practice”[tiab] OR “rapid cycle deliberate practice”[tiab] OR “learner faculty dyad”[tiab] OR scaffolding[tiab] OR cueing[tiab] OR modeling[tiab] OR “Listening in”[tiab] OR “situated learning”[tiab] OR “active experimentation”[tiab] OR apprentice*[tiab] OR teach*[ti] OR train*[ti] OR instruct*[ti] OR micro-debriefing[tiab] OR microdebriefing[tiab] OR “micro debriefing”[tiab]) |

Search Strategy v 2.0

| Database | Search paramaters |

|---|---|

| Updated PubMed Search Strategy (n=865) | (“Medical simulation” OR “nursing simulation” OR “Simulation-based” OR “Healthcare simulation” OR “simulated patient” OR “simulated patients” OR “simulated person” OR “simulated people” OR “simulated participant” OR “simulated participants” OR “simulation patient” OR “simulation patients” OR “simulation person” OR “simulation people” OR “simulation participant” OR “simulation participants” OR telesimulation OR “simulation educator” OR Simulation*) ((during AND simulat*) OR “within event” OR “within-event” OR “within-event learning” OR “during simulation” OR “during the simulation” OR “during the clinical scenario” OR “during the clinical simulation” OR micro-debriefing OR microdebriefing OR “micro debriefing” OR “during simulated patient” OR “during the simulated scenario” OR “Intra-simulation learning” OR “intrasimulation” OR (debrief* AND during AND simulation*) OR “In-scenario instruction(”adaptive” OR “facilitate” OR “supervision”OR “engage” OR motivate[tiab]) AND simulation[tiab]) (Facilitation OR Support OR Guidance OR coaching OR “deliberate practice” OR “Rater and Learner Dyad” OR “learner centered learning” OR “learner centeredness” OR “learner faculty dyad” OR scaffolding OR “knowledge convey” OR “knowledge conveyance” OR cueing OR modeling OR “Cognitive load” OR “Listening in” OR “situated learning” OR “active experimentation” OR apprenticeship* OR learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) AND (learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) |

| CINAHL Search Strategy (n=1107) 2 duplicates |

(“Medical simulation” OR “nursing simulation” OR Simulation-based OR “Healthcare simulation” OR “simulated patient” OR “simulated patients” OR “simulated person” OR “simulated people” OR “simulated participant” OR “simulated participants” OR “simulation patient” OR “simulation patients” OR “simulation person” OR “simulation people” OR “simulation participant” OR “simulation participants” OR telesimulation OR “simulation educator” OR Simulation*) ((during AND simulat*) OR “within event” OR within-event OR “within-event learning” OR “during simulation” OR “during the simulation” OR “during the clinical scenario” OR “during the clinical simulation” OR micro-debriefing OR microdebriefing OR “micro debriefing” OR “during simulated patient” OR “during the simulated scenario” OR “Intra-simulation learning” OR intrasimulation OR (debrief* AND during AND simulation*) OR “In-scenario instruction(adaptive”” OR facilitate OR “supervisionOR “engage”” OR (TI motivate OR AB motivate)) AND (TI simulation OR AB simulation) (Facilitation OR Support OR Guidance OR coaching OR “deliberate practice” OR “Rater and Learner Dyad” OR “learner centered learning” OR “learner centeredness” OR “learner faculty dyad” OR scaffolding OR “knowledge convey” OR “knowledge conveyance” OR cueing OR modeling OR “Cognitive load” OR “Listening in” OR “situated learning” OR “active experimentation” OR apprenticeship* OR learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) AND (learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) |

| Embase Search Strategy (n=251) 2 duplicates |

(‘Medical simulation’ OR ‘nursing simulation’ OR Simulation-based OR ‘Healthcare simulation’ OR ‘simulated patient’ OR ‘simulated patients’ OR ‘simulated person’ OR ‘simulated people’ OR ‘simulated participant’ OR ‘simulated participants’ OR ‘simulation patient’ OR ‘simulation patients’ OR ‘simulation person’ OR ‘simulation people’ OR ‘simulation participant’ OR ‘simulation participants’ OR telesimulation OR ‘simulation educator’ OR Simulation*) ((during AND simulat*) OR ‘within event’ OR within-event OR ‘within-event learning’ OR ‘during simulation’ OR ‘during the simulation’ OR ‘during the clinical scenario’ OR ‘during the clinical simulation’ OR micro-debriefing OR microdebriefing OR ‘micro debriefing’ OR ‘during simulated patient’ OR ‘during the simulated scenario’ OR ‘Intra-simulation learning’ OR intrasimulation OR (debrief* AND during AND simulation*) OR ‘In-scenario instruction(adaptive”’ OR facilitate OR ‘supervisionOR “engage”’ OR motivate:ti,ab) AND simulation:ti,ab (Facilitation OR Support OR Guidance OR coaching OR ‘deliberate practice’ OR ‘Rater and Learner Dyad’ OR ‘learner centered learning’ OR ‘learner centeredness’ OR ‘learner faculty dyad’ OR scaffolding OR ‘knowledge convey’ OR ‘knowledge conveyance’ OR cueing OR modeling OR ‘Cognitive load’ OR ‘Listening in’ OR ‘situated learning’ OR ‘active experimentation’ OR apprenticeship* OR learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) AND (learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) |

| PsycINFO Search Strategy (n=656) 1 duplicates |

(“Medical simulation” OR “nursing simulation” OR Simulation-based OR “Healthcare simulation” OR “simulated patient” OR “simulated patients” OR “simulated person” OR “simulated people” OR “simulated participant” OR “simulated participants” OR “simulation patient” OR “simulation patients” OR “simulation person” OR “simulation people” OR “simulation participant” OR “simulation participants” OR telesimulation OR “simulation educator” OR Simulation*) ((during AND simulat*) OR “within event” OR within-event OR “within-event learning” OR “during simulation” OR “during the simulation” OR “during the clinical scenario” OR “during the clinical simulation” OR micro-debriefing OR microdebriefing OR “micro debriefing” OR “during simulated patient” OR “during the simulated scenario” OR “Intra-simulation learning” OR intrasimulation OR (debrief* AND during AND simulation*) OR “In-scenario instruction(adaptive”” OR facilitate OR “supervisionOR “engage”” OR motivate.ti,ab.) AND simulation.ti,ab. (Facilitation OR Support OR Guidance OR coaching OR “deliberate practice” OR “Rater and Learner Dyad” OR “learner centered learning” OR “learner centeredness” OR “learner faculty dyad” OR scaffolding OR “knowledge convey” OR “knowledge conveyance” OR cueing OR modeling OR “Cognitive load” OR “Listening in” OR “situated learning” OR “active experimentation” OR apprenticeship* OR learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) AND (learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) |

| Web of Science Search Strategy (n=2506) | (“Medical simulation” OR “nursing simulation” OR Simulation-based OR “Healthcare simulation” OR “simulated patient” OR “simulated patients” OR “simulated person” OR “simulated people” OR “simulated participant” OR “simulated participants” OR “simulation patient” OR “simulation patients” OR “simulation person” OR “simulation people” OR “simulation participant” OR “simulation participants” OR telesimulation OR “simulation educator” OR Simulation*) ((during AND simulat*) OR “within event” OR within-event OR “within-event learning” OR “during simulation” OR “during the simulation” OR “during the clinical scenario” OR “during the clinical simulation” OR micro-debriefing OR microdebriefing OR “micro debriefing” OR “during simulated patient” OR “during the simulated scenario” OR “Intra-simulation learning” OR intrasimulation OR (debrief* AND during AND simulation*) OR “In-scenario instruction(adaptive”” OR facilitate OR “supervisionOR “engage”” OR (TI=motivate OR AB=motivate)) AND (TI=simulation OR AB=simulation) (Facilitation OR Support OR Guidance OR coaching OR “deliberate practice” OR “Rater and Learner Dyad” OR “learner centered learning” OR “learner centeredness” OR “learner faculty dyad” OR scaffolding OR “knowledge convey” OR “knowledge conveyance” OR cueing OR modeling OR “Cognitive load” OR “Listening in” OR “situated learning” OR “active experimentation” OR apprenticeship* OR learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) AND (learn* OR teach* OR educat* OR train* OR instruct*) |

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| 1. Explicitly addresses instruction/support provided during a simulation event/activity. 2. Instructional support provided by attendings, fellows, standardized or simulated participants, peers, near peers, or a computer or simulator. 3. Remote support such as teleguidance or Telementoring. 4. Simulated learning contexts include in-laboratory, in situ, augmented reality, virtual reality, scenario-based simulations, role plays, procedural-based simulations, or telesimulation. 5. Studies that focus on rapid cycle deliberate practice because this approach includes support during simulation practice. 6. Original research (i.e., Qualitative, Quantitative, Mixed- or Multi-Method). 7. Systematic reviews (e.g., meta-analysis, narrative analysis, scoping review). 8. Instructional support can be given verbally, physically, auditorily, or through demonstrations as long as it occurs or is accessible during simulation engagement. 9. All languages. |

1. Focuses on post-simulation debriefing only. 2. Focuses on pre-simulation briefing only. 3. Not Research (e.g., Commentary, Perspective, Letter to the Editor). 4. Conference paper/poster/abstract not associated with paper. 5. Focuses on a simulation innovation or simulation curriculum that does not emphasize within simulation instructional support or guidance given during simulation participation. 6. Not healthcare simulation. 7. Technical Report |

| Exclusion Reason | Operational Definition |

|---|---|

| Describes the design of a decision support tool that will eventually be used in the clinical setting. | This category includes articles that focus on descriptions of the design of a decision support tool for the clinical setting. Decision support tools, also called patient decision aids, support shared decision-making by making explicit treatment, care, and support options. They provide evidence-based information about the associated benefits/harms and help patients consider what matters most to them concerning the possible outcomes, including doing nothing. Although decision support tools scaffold decision-making, these articles do not focus on employing the tool to promote learning during simulation. Articles that employ simulation as a research or evaluation method to study the usability or efficacy of a decision support tool should be excluded. |

| Evaluates the development/implementation of a new simulation curriculum that does not include scaffolding. | This category is for articles that describe a curriculum or simulation activity that does not emphasize any of the goals of scaffolding. |

| Describes the development of a new simulator or model that does not include scaffolding. | This category is for articles whose primary focus is to describe the development of a new simulator or model that does not emphasize any of the goals of scaffolding. |

| Post-simulation guidance only. | This category is for articles primarily focused on providing guidance and support after the simulation, such as post-simulation feedback or debriefing. |

| Pre-simulation guidance only. | This category is for articles primarily focused on providing guidance or support before the simulated activity, such as pre-simulation readings, pre-simulation videos/models to view, or pre-briefing. |

| No guidance or support provided during simulation engagement. | This category is for articles that do not include any description of guidance and support provided during the simulated encounter. |

| Uses simulation to test a clinical application, device or tool. | This category is for articles that use simulation as a research or evaluation method. |

| Single mention of guidance or support without a definition or description. | This category is for articles that include a single mention of guidance and support, such as instruction provided by faculty or other experts (usually described in the method section). However, no additional detail is provided, no theoretical framework is espoused, and no additional description is provided in the paper’s discussion. |