Embedded participants (EPs) are essential in most high-quality health simulation programmes, particularly in undergraduate education. The expertise and experience EPs bring to simulation can significantly optimize and enhance realism of learning environments and guide learners as they develop their technical and behavioural skills. This proposed qualitative, observational study will explore, in detail, the functions and roles of EPs from the perspectives of the EP, learners and other members of the simulation team. The primary aim is to understand and describe the different functions and roles of EPs when engaging in simulation scenarios with varying learner groups and learner capabilities.

Informed and influenced by Role Theory and the Guiding, Intermediating, Facilitating and Teaching conceptual framework, this protocol describes an exploratory qualitative observational study using semi-structured interviews and video-reflexive strategies to understand what EPs’ functions and roles are, and how they fulfil these roles. EPs will participate in a series of structured simulation scenarios involving varying learner groups of varying capability and members of the simulation team. The scenarios will be audio-visually recorded. Data will be collected through interviews and observation of recorded scenarios. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis will inform the analysis of interview data.

Various roles are assumed in health simulation contexts. Understanding these roles, and how people function in these roles is vital for ongoing quality improvement, the establishment of new simulation services and the development and deployment of appropriate faculty development.

Health simulation programmes excel with the input and support of people with diverse expertise and experience. Different roles are adopted (e.g. simulated patients/participants [SPs], simulation technicians, debriefers and embedded participants [EPs]) to facilitate scenarios with learners at varying times in their professional development and who have varying capability to perform different skills [1,2]. People will function in these roles in various ways to achieve the intended goals of each simulation. EPs are particularly significant in undergraduate contexts in which learners are relatively inexperienced in navigating clinical environments and require guidance as they develop relevant technical and behavioural skills. It is this group of simulation experts that is the focus of this proposed study.

EPs have been identified by many names, including the now outdated term ‘confederate’, denoting their alliance with simulation facilitators [1]. Other terms include accomplices, embedded actors and simulated healthcare professionals [2,3]. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [4] and the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning [3] define an EP as someone ‘… trained or scripted to play a role in a simulation encounter in order to guide the scenario and may be known or unknown to the participants; guidance may be positive or negative, or a distractor based on the objectives, level of the participants, and the needs of the scenario’ [3] While we acknowledge the above definition, for the purposes of this study, and in our context, EPs are health professionals who fulfil the role of a healthcare worker in simulation scenarios to support learners (where required) and the progression of simulated scenarios.

EPs have been examined in several studies. Previous research indicates that EPs can enhance realism, stimulate learner engagement, facilitate scenario progression [5–7], protect scenario integrity, maintain alignment with the learning activity’s objectives [8,9] and protect SPs and learners [2,10]. What is not yet well understood is how EPs make decisions about when and how to intervene or abstain from intervening. Exploration of the EP role (i.e. the patterned and characteristic social interactions of EPs in the context of health simulation [11,12]) with a specific focus on how EPs function (i.e. what do EPs think and do to fulfil their role) would be invaluable for ongoing professional development for individual EPs, and faculty development through training of new EPs.

As the various modalities of simulation in healthcare education continue to be adopted [13,14], there is a need to better understand how and in which circumstances EPs contribute to simulations. This project has been designed to distinguish and describe the functions and roles of EPs in the various relationships they have with different learners and members of the simulation team. It has been designed to elicit participants’ specific role goals, strategies, decision-making processes and attributes.

The theoretical foundation selected to underpin this research is Role Theory. Role Theory comprises several theories often used in sociology to explain the formation of individual behaviours in social contexts based on one’s ability to recognize, understand, interpret and respond to those contexts [11,15,16]. Role theory has recently been used to support the examination of the debriefer role in health simulation scenarios [12]. Roze des Ordons adopted the symbolic-interactionist definition of a ‘role’ which states that roles are ‘an organized set of principles that guide behavior, and of which the details are shaped through interactions with others in a particular social context’ [12]. The application of this theory as a lens for examining how EPs function should afford us with the language and theoretical framing to describe the EP role with nuance and depth.

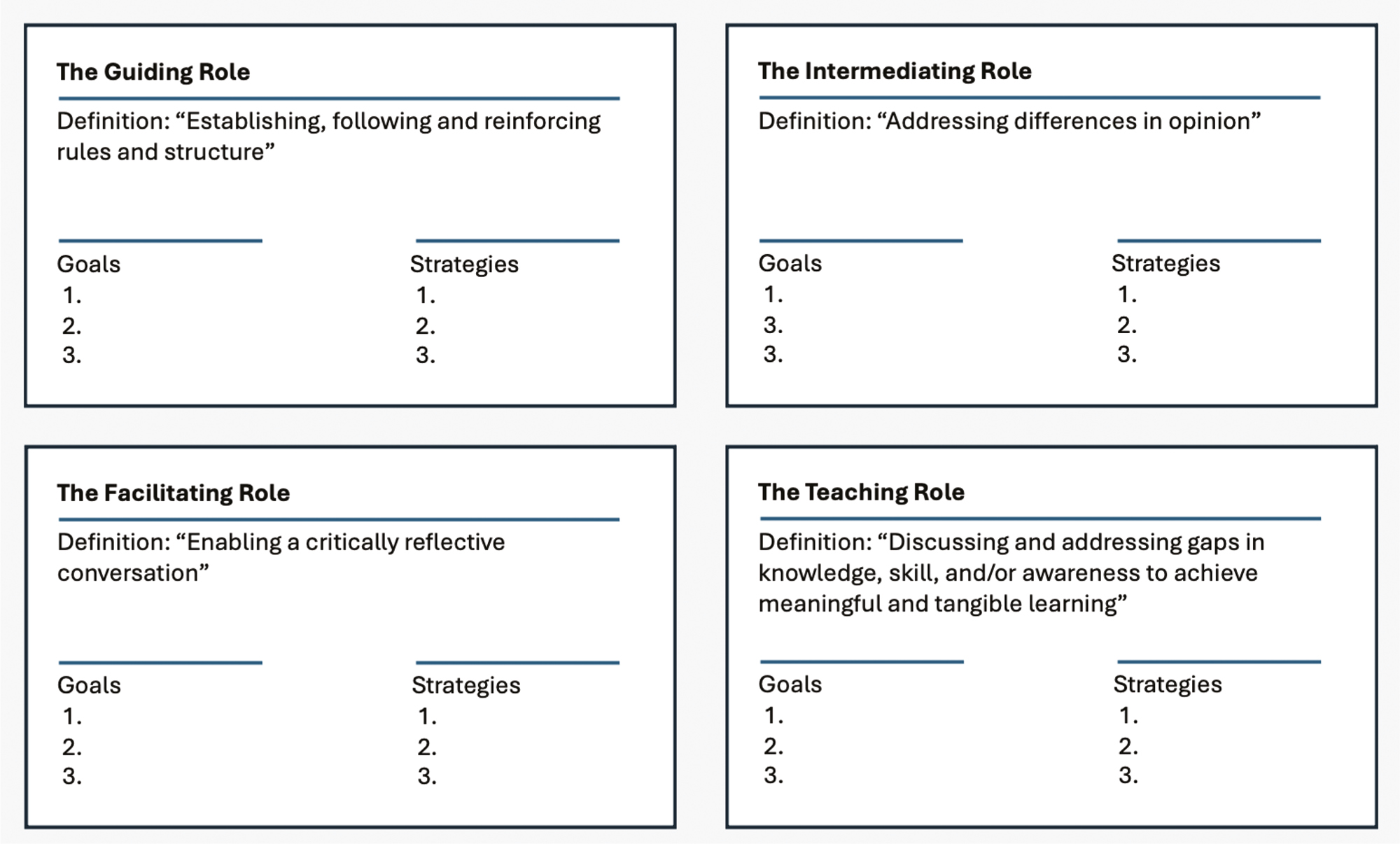

As well as a theoretical foundation, our study design is influenced by the Guiding, Intermediating, Facilitating and Teaching (GIFT) conceptual framework developed by Des Ordons [12] and Role Theory [15]. The GIFT framework describes four types of roles that debriefers described and were observed to adopt. The framework that is used includes three sections: a definition of the role, the goals debriefers have when working in each debriefing role and the strategies debriefers use to achieve the goals in each role [12] (see Figure 1). While the specific strategies used by EPs in simulation scenarios are likely to differ from those adopted by debriefers, we anticipate cross-over in the descriptions of over-arching role domains and potentially with goals that debriefers and EP share. We anticipate divergence within the goals and strategies sections of the GIFT framework, when it is applied to EPs, but believe the framework has potential utility for exploring the unique features of this group of simulationists.

GIFT conceptual framework as described by Roze des Ordons et al. (2022).

This study aims to examine and describe the different functions and roles of EPs when engaging in simulation scenarios in an Australian tertiary education health simulation centre. Specifically, this study aims to address the following questions:

1.What are the functions and roles of EPs when engaging in simulation scenarios with varying learner groups and varying learner capabilities?

2.What are the functions and roles of EPs in relation to other members of the simulation team (e.g. SPs, other EPs, simulation technicians, educators, debriefers)?

3.How do the different EP functions and roles relate to one another?

4.How do the functions and roles of EPs compare with the debriefer’s roles and functions understood through the lens of GIFT and the role-related concepts such as role strain, overload, ambiguity, or sharing?

5.How do simulation team members and learners perceive their relationship with EPs?

This study will take place at Adelaide Health Simulation (AHS) – a health simulation unit of the University of Adelaide, Australia. AHS is accredited as a simulation centre by the Society for Simulation in Healthcare and is equipped to conduct concurrent structured simulation scenarios and collect high-quality audio and video recordings (each room has in-built video and audio recording equipment). The high-quality facility enables a controlled research environment that allows for the replicability of the structured simulation component of the proposed study.

AHS employs registered health professionals (e.g. Registered Nurses, Medical Doctors) as expert simulation educators and simulation fellows in both full-time and part-time capacities. These simulationists are largely responsible for designing and delivering simulation activities to meet the learning outcomes of various health professions students (e.g. undergraduate and post-graduate medical, nursing and psychology students). The AHS simulation educators and fellows fulfil the EP role in almost all circumstances. As the creators of the simulations, EPs are intimately aware of the learning outcomes and anticipated flow of the scenario. They are responsible for briefing SPs and often will be responsible for briefing participants (this role is shared between the EP and the debrief facilitator). There are some academics from schools within the University (for instance, the nursing and medical schools) who are developing simulation expertise and who also work in the EP role.

In our context, the EP role is distinct from the SP role and the debriefing role. SPs are integral to our programme but do not come from health professions backgrounds. SPs perform the roles of the patients and patient relatives. Most frequently, the debrief facilitator will be co-located with the observer group, and not be an active participant in the simulation scenario. This affords the debriefer the opportunity to observe all participants and to prompt reflection with the observer group.

Faculty development for EPs is undertaken through several mechanisms, including peer observation, peer feedback, engagement in weekly journal club discussions, and attendance at local, national and international conferences. There is not a specific course that EPs attend, rather they build their skills over time, and with support and guidance from the broader AHS team.

In this study, the functions and roles of EPs will be viewed from different perspectives using a qualitative, observational, exploratory design. Each EP participant will be interviewed, and will complete six simulated scenarios where they will perform, as usual, in their EP role with learner groups of varying type and capacity to meet set learning outcomes, and then re-interviewed with the assistance of scenario recordings using a video-reflexive approach. Ancillary participants, including simulated learners, SPs, simulation facilitators and simulation technicians will also be interviewed. Data from video recordings of the simulated scenarios and from interviews will be used to address the research questions.

Three groups of participants will be invited to participate in this study – EPs, simulation team members, and learners. The first two groups will include AHS employees, who have been separated here for the purpose of the research project. Group 1 will comprise 6–10 participants EPs who have worked as EPs for more than six months. Group two will include other simulation team members who are employed to work in health simulation in the roles of SPs, simulation technicians and simulation facilitators. The learner group (Group 3) will include enrolled students from pre-registration nursing and medicine programmes who will be embedded into the scenarios with instructions for how to behave and respond in the simulated scenarios. For the purpose of this study, Group 3 will be supported and ‘primed’ to behave in specific ways within the scenario, allowing EPs to work with learners of varying capabilities. There is no expectation that learners will indeed meet learning outcomes in these scenarios – they will be present to enable this research project to be conducted.

Sampling for Group 1 and 2 participants will be purposive, with invitations extended to AHS employees via email. It is anticipated that between 6–10 EPs and 8–14 simulation team members will be recruited into the project. As the nature of the study requires all participants to be present on a designated day, the number of recruited participants will be determined by the availability of eligible participants on the designated study day. As a qualitative study, we do not anticipate requiring a larger sample of participants from these groups to produce sufficient data to address the research questions for this study.

Group 3 will consist of a sample of convenience, with invitations emailed to students via the Adelaide Nursing School (ANS) and Adelaide Medical School (AMS). The sample size for this group is directly related to the number of planned simulations, where there will be two learners per simulation scenario (total n = 12) plus an additional two students who will be ‘spares’ in case of illness or incapacitation of the initially selected participants (total n = 14). In total, there will be between 29 and 36 participants recruited into this project.

People will be eligible to participate in Group 1 of this study if they have a clinical background (i.e. nurses, physicians, fellows) and have worked in the EP role at AHS for at least 6 months. People will be eligible to participate in Group 2 of this study if they have a permanent, fixed term or casual contract with AHS to work in other roles to support simulation scenarios, including SPs, simulation facilitators and simulation technicians. Eligible participants for Group 3 will include pre-registration students from the ANS and AMS. We will be seeking five final-year nursing students (either from the Bachelor of Nursing or Master of Clinical Nursing cohorts) and nine students from the medical programmes. These students may be from any year level between four and six. Pre-requisite to participation in the study will be the signing of a research consent form, as approved by the institution’s human research ethics committee.

Participants who meet the inclusion criteria for Groups 1 and 2 will be invited to participate in the study via the generic AHS email account by the AHS professional staff team. These staff members are not eligible to participate in the project and have agreed to distribute an email to staff. Participants who meet the inclusion criteria for Group 3 will be invited to participate in the study via an email that will be sent to the respective schools.

When prospective participants respond, study information sheets and consent forms will be provided containing the purpose and structure of the study, the extent of participant involvement, potential risks and anticipated benefits, and compensation. They will be offered a time to meet and discuss the project and project logistics.

Written informed consent will be collected before each interview. Ongoing consent will be confirmed with participants verbally throughout the different time periods of the study.

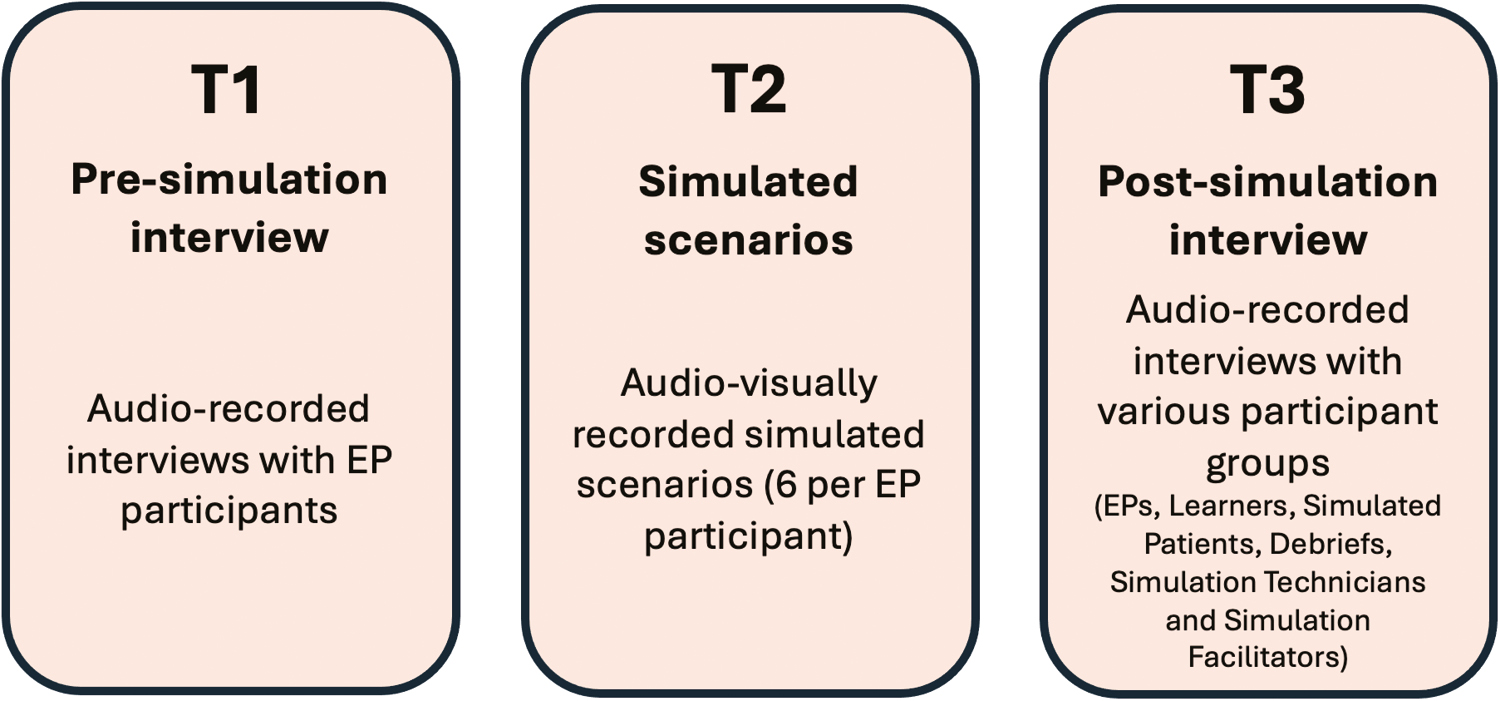

In this qualitative observational exploratory study, data will be collected at three time points, as illustrated in Figure 2. This data collection plan follows a similar structure employed by Roze des Ordons et al. [12], and shares elements with Taylor et al.’s recent study with an obstetric team [17].

Timepoints for data collection.

At Timepoint 1 (T1), participants from the EP group will participate in a 20- to 30-minute pre-simulation semi-structured interview facilitated by JP. There will be six main questions with follow-up questions to explore how EPs describe their functions and roles (Supplemental File 1a). Participants will be interviewed using the Appreciative-Inquiry approach which has been found to stimulate, encourage and facilitate storytelling based on personal experience [18]. Interviews will be audio recorded and professionally transcribed for analysis.

At Timepoint 2 (T2), EP participants will perform their EP role in six planned, consecutive simulation scenarios, where they will encounter learner participants from varying undergraduate programmes who have varying capabilities to meet the prescribed learning outcomes. Scenarios will be audio-visually recorded for video-reflexive interviews (i.e. interviews where participants will view recordings of their performance and comment on what they see) with EPs at Timepoint 3 (T3).

At T3, EPs will be invited to a 20- to 30-minute post-simulation video-reflexive interview. Using videos, participants will have the opportunity to observe, reflect and comment on events in which they have just participated [19,20]. Three to four selected segments of recordings that appear to be of significance will be presented in these interviews, and EP participants will be asked to reflect on their functions and roles in the simulated scenarios (Supplemental File ib). Moments of significance in this project will include direct actions and behaviours initiated by EPs, verbal interactions with learners, and times when EPs appear to withhold or withdraw from the scenario. All other participants (from Groups 2 and 3) will be invited to participate in a semi-structured interview where they will be asked to reflect on the role of the EP and their interactions with people in this role (Supplemental File 1c). Interviews at T3 will be conducted by JP and MT and be audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis.

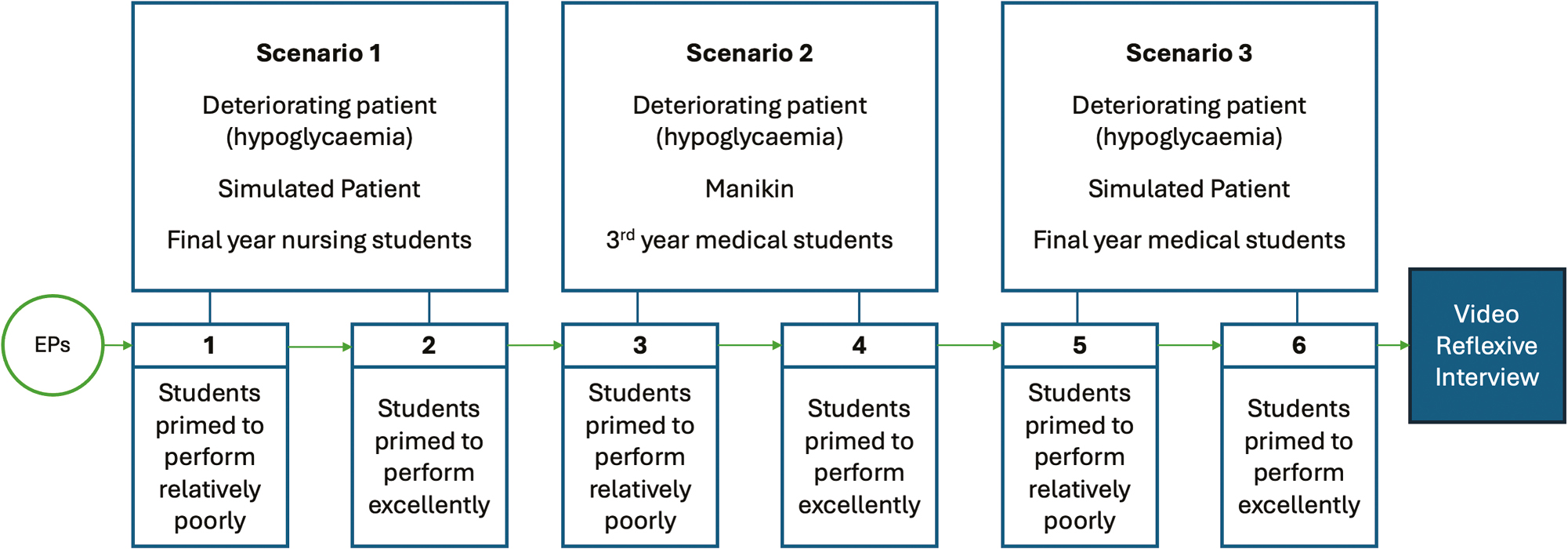

EPs will participate in six 5- to 10-minute simulated scenario stations (see Figure 3 for participant flow-through scenarios). These scenarios have been designed specifically for this project, are not part of any particular curriculum and are not linked with learner participants’ assessments or programmes. Participants will be required to recognize and respond to a patient who is experiencing an altered conscious state as a result of hypoglycaemia. This stem for a simulation scenario is reasonably typical for undergraduate health professions simulation.

Participant flow through simulated scenarios.

The simulated scenarios have been adapted for three learner groups: final-year pre-registration nurses, third-year medical students and sixth-year medical students. EPs will go through each of these three scenarios twice. Because we are interested in investigating how EPs function in their roles when they have learners of varying capability, we will be providing instructions to learner participants about how well or poorly to perform in the scenarios – that is, we will be ‘priming’ them to behave in specific ways. Including relatively good and relatively poor student performance serves as a variable to elicit different responses from EPs.

Three groups of learner participants will be primed to perform the scenario poorly (i.e. prior to the simulation, they will be instructed to purposefully delay the recognition of deterioration and to poorly manage the deteriorating patient). The other three groups of learner participants will be primed and coached to perform the scenario well (i.e. they will be expected to recognize and respond promptly and appropriately and as a team when there are signs of patient deterioration). The EPs will not be aware of the priming that has occurred with learner participants (i.e. they will be blinded to this element of the study).

All scenarios will be audio-visually recorded via a purpose-built system that exists in all simulation and teaching rooms at AHS, and that is routinely used to record clinical assessments and other formative simulations where learners will benefit from watching their performance in simulation. All participants in this proposed study are familiar with and have previously been filmed with this system.

SPs will be employed in four of the stations (Year 3 pre-registration Nursing and Year 6 Medicine). A manikin will be used in two stations with the Year 3 Medicine stations. As these different modalities are routinely used in simulation services, we would like to capture reflections and observations relating to the functions and roles of EPs when SPs vs manikins are representing patients.

EPs will receive their brief on the scenario day, as per usual practice. EPs will not be primed to the different learner groups to observe and explore their ability to adapt to these varying performance levels. No other participant groups will have reduced disclosure of details of case scenarios. All other participants will be primed for the scenarios ahead of the day that they will be run.

Data analysis will occur in three phases. Firstly, transcripts from EP interviews will be read and re-read for data familiarization. The first three interviews will be independently coded by all authors, using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) methodology. IPA is a qualitative methodology originally used in psychology and greatly influenced by phenomenology, hermeneutics and ideography [21,22]. This analytic process facilitates sense-making of participants’ lived experiences by bringing past experiences and assumptions to the present and using them to interpret and develop a comprehensive understanding of phenomena. Codes from all authors will be compared, and a coding framework established. The remaining transcripts will be analysed, and the coding framework amended where necessary. Coded data will be organized into themes, based on prominent patterns and significant findings [23]. The author team will meet regularly to review and compare codes, themes and concepts, addressing discrepancies and overlaps to reach a consensus.

In Phase 2, findings from the above inductive analysis will be viewed with the intention of determining the ‘fit’ of data to the GIFT framework. Data related to the goals and strategies that are articulated by participants will be explored with the intent of determining whether the GIFT framework adequately accommodates findings from this study, if adaptations are needed to accommodate findings from this study or whether it is not a good fit. In the final third phase, video recordings of scenarios will be observed, with the view to documenting observed behaviours that relate to the qualitative findings from Phases 1 and 2. The methods for how this will occur and what data points will be recorded will be determined by findings in Phases 1 and 2, and will be reported in the final project manuscript.

In line with a constructivist approach, our analysis is a product of the reflexive interplay between the data itself, the guiding frameworks used [12,15], and the diverse perspectives of the study team. The team comprises JP who is a 2024 Post-Doctoral Fellow at AHS and who has a substantive role in the College of Nursing at the University of Philippines, Manila. JP has a background in nursing practice, nursing education and patient safety. JP has experience undertaking both quantitative and qualitative research. MT is a Research Fellow at AHS. MT has an academic background in philosophy and sociology. He has experience in theory development and qualitative research. ED is the Research Program Lead at AHS. ED is an experienced researcher and supervisor of qualitative and mixed-methods research projects.

Whilst prospective EP participants work in the same team, members of the research team do not have any direct line management responsibilities for EPs, have not trained EPs, nor have they worked with EPs as formal learners. The catalyst for conducting this project was work was a curiosity for how to support new and current EPs in their roles. A formal research project was selected as an optimal vehicle for examining with close a specific attention, the work that EPs do, and the thoughts and reflections they have regarding this work.

To enhance trustworthiness, reduce bias and optimize transparency, this protocol was developed and submitted for peer review and publication. In qualitative research, this formal process is not often undertaken, but is a process that we argue should be considered more frequently [24].

A gap in evidence lies in understanding how EPs enhance healthcare simulation experiences for learners and other simulation participants [2,7,10,25]. Through a multi-perspective exploratory approach, this study will extensively describe the different functions and roles of EPs when engaging with learners and other participants in simulation scenarios in an Australian tertiary education health simulation centre. Of particular importance are the interpersonal relationships, interactions and communication that EPs have with learners and other simulation participants, and the responses, decisions and transitions they make as simulation scenarios progress.

This protocol has been submitted for peer-review and publication to enhance the transparency and rigour of the project. Whilst not often published, protocols for qualitative research are important in the process of producing credible and transparent research findings [24].

The anticipated outcomes of this study include gaining a better understanding of the interconnections and interactions EPs have with learners and other participants in simulation, the experiences they have as part of a simulation team, and the extent to which their contribution to student learning aligns with frameworks for teaching roles and activity [12,15]. The results and analysis will enable us to develop and propose a detailed holistic framework that captures the distinct functions and roles that EPs perform in simulation-based education. The framework will not only inform simulation-based education, practice and research, it will also serve as a valuable resource for professional development and advocacy for EPs.

The study acknowledges the potential limitations due to its single-cohort design, context specificity and risks for bias. The study’s findings may not be universally applicable to centres with varying resources because of the single-cohort design. The study’s methodology and context specificity could also introduce limitations, given the variations in the employment of EPs in simulation scenarios, different modalities (i.e. SPs, manikins, hybrid, VR), and diverse learner demographics (including post-graduates and health professionals). To tackle these issues, the study will involve a range of learners and ensure consistent scenario contexts across various modalities and setups. To address potential observation and respondent bias, decisions have been made to include participants who are accustomed to being video recorded, to have interviewers with limited prior knowledge of participants, and to follow a semi-structured interview guide to elicit genuine responses.

The authors would like to thank Adelaide Health Simulation for administrative and resource support.

ED and JP collaborated in the study conception and design. JP, ED and MT developed the protocol, revisions, and the final manuscript. All authors will participate in data collection and analysis.

This project is part of the post-doctoral research of JP, funded by Adelaide Health Simulation.

None declared.

This proposed study has been reviewed and approved by The University of Adelaide Lower Risk Ethics Committee (HREC 2024-157). Project outcomes will be made publicly available via academic publications (journal article(s)), conference presentations, symposiums, and faculty development resources.

There are no foreseeable perceived or actual financial competing interests to declare.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.