The patient safety agenda suggests that simulation can aid professional capability development, particularly leadership and communication skills [1]. Complex non-technical skills required by effective leaders may be improved by using trained simulated participants (SP) within leadership scenarios. However, evidence in this area is lacking. This study explored the student perspectives of simulation as an educational tool for leadership development in a postgraduate module.

Ethical approval was granted by Oxford Brookes University.

A half-day pilot study was co-created by simulation and leadership experts and delivered to 15 international students from diverse backgrounds enrolled on a leadership module. The scenario utilised a trained SP portraying the role of an employee who was part of an organisational change management intervention. The participants were leading the change process. Additional pre-brief time was needed to build psychological safety within the group. The scenario was paused when learning moments were identified, to allow students and observers to participate in the discussions of leadership concepts [2]. There was an overall group debrief at the end. A focus group exploring the student perspectives of their learning experience was conducted following this debrief. The data was audio recorded, anonymously transcribed and analysed.

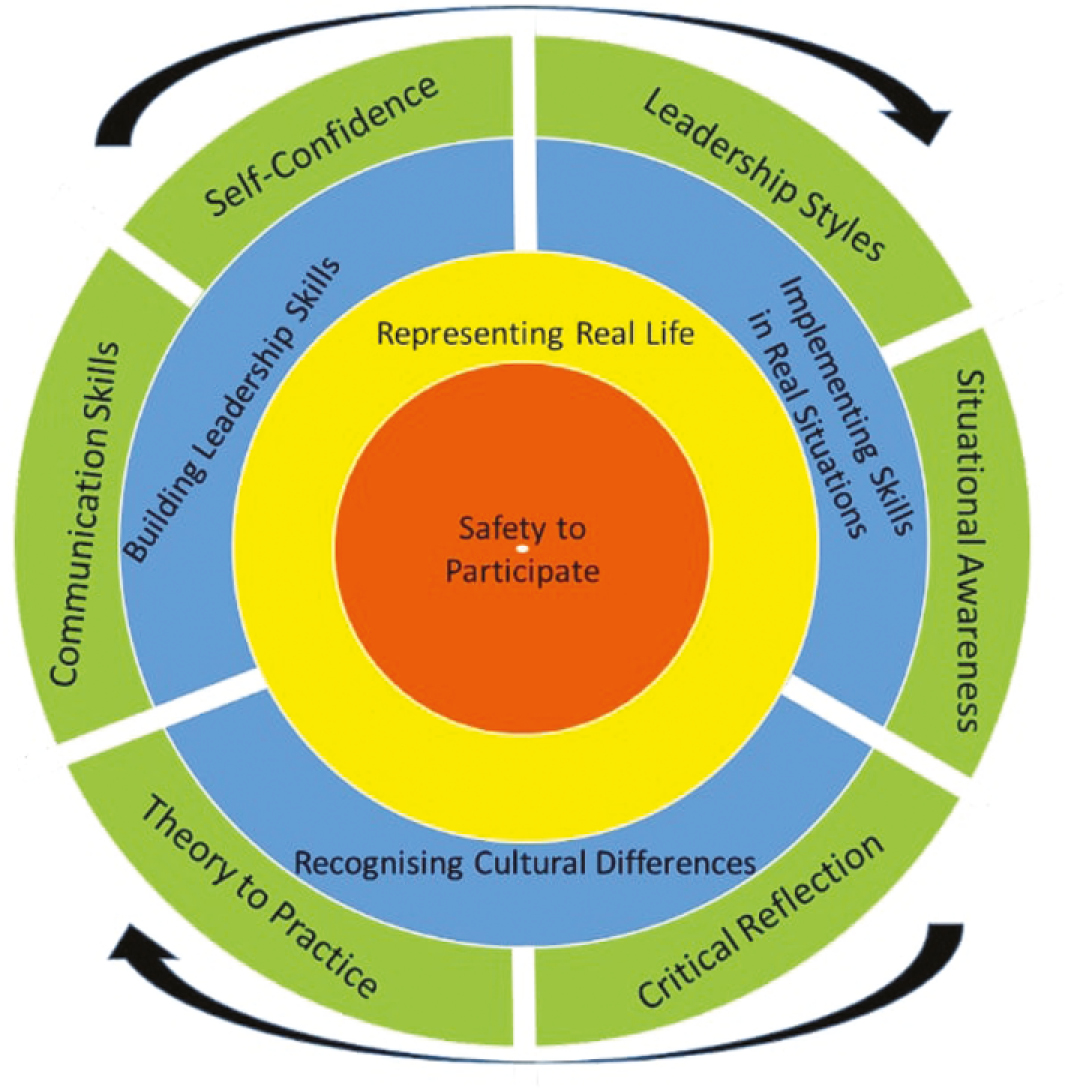

Thematic analysis of the focus group data revealed parallels with current literature such as providing safety to participate; representing real life; enabling application of theory to practice and building leadership skills [3]. Analysis also highlighted the recognition and impact of cultural differences on the awareness and use of leadership styles.

“So I think that it’s good to know that at any point we can take something from this toolbox and choose, maybe this didn’t work in the past, so maybe I can try this other style.”

“For me the strengths were that we are all culturally diverse from our discussions, so what we believe or feel about competence as a leader is different for everyone. This made the discussion quite valuable and to understand everyone’s perspective on the problems of leadership.” The study findings were mapped into a conceptual model (Figure 1-A82).

Simulation with a trained SP in a psychologically safe and realistic environment was an effective and culturally competent way to apply relevant leadership theory and skills, within health and social care postgraduate training. This simulation pilot facilitated critical discussions that recognised cultural differences as well as the benefits and challenges of implementing western styles of leadership in other countries.

Authors confirm that all relevant ethical standards for research conduct and dissemination have been met. The submitting author confirms that relevant ethical approval was granted, if applicable.

1. Health Education England. Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/National%20Strategic%20Vision%20of%20Sim%20in%20Health%20and%20Care.pdf.

2. Butler C, McDonald R, Merriman C. Origami debriefing model: unfolding the learning moments in simulation. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning. 2017;4(3):150–151 [cited 2024 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8936804/.

3. Botma Y. Nursing student’s perceptions on how immersive simulation promotes theory–practice integration. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences [Internet]. 2014;1:1–5. Available from: https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S221413911400002X?token=BAFD12156F062B27BBF46DF3961F1C5D801028B37EB9DD3B3B4F9843119ABF0F1156AD77018EEE34FF679505883A85B7.