The Newborn Intensive Care Unit (NICU) can be an alienating and intimidating environment for parents. Having a baby in the NICU is stressful, and there is emerging work documenting the profound effect it can have on parental mental health [1]. Parents may experience negative and isolating emotions and may feel unable to help their children [2]. Neonatal staff can empower parents to be involved in their baby’s care. This is important in promoting bonding [3,4]. One key element of providing family-integrated care is parental involvement in infant feeding; however, parents may find the prospect of a nasogastric tube (NGT) feeding intimidating.

Simulation is increasingly being recognized as a useful training modality for parents, empowering them to gain new skills and confidently participate in their baby’s care. A selection of preterm infant and term infant manikins were available through the regular simulation programme on NICU. There were no manikins designed to allow gastric aspirate to be obtained, pH to be tested or feed to be administered. These features are key to the process of safe NGT feeding. Consequently, a bespoke NGT feeding simulation manikin needed to be designed from the manikins available on the unit.

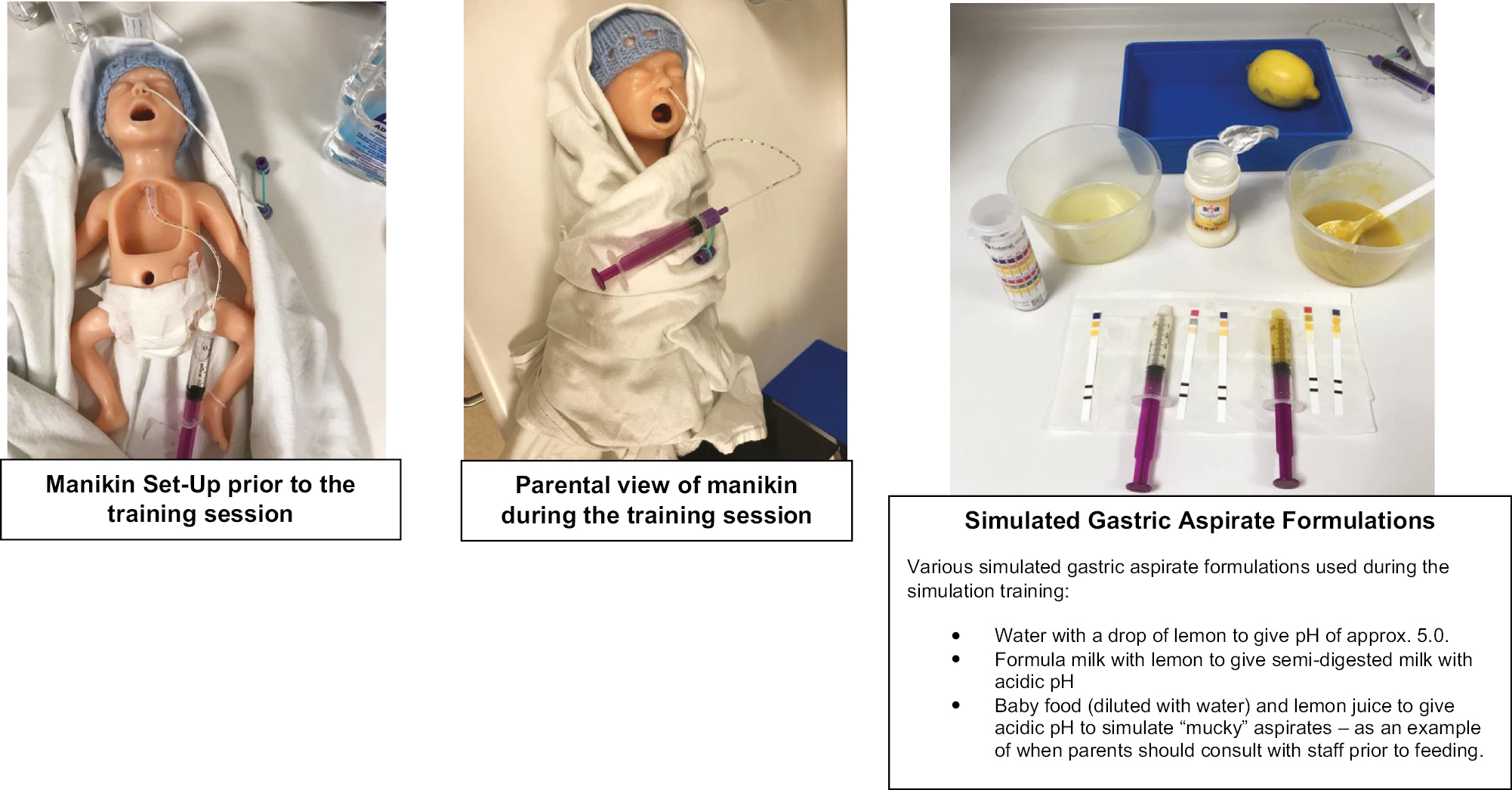

After reviewing the manikin options available, it was felt that the extreme preterm infant Simulaids manikin [5] with the removable chest block would be the most appropriate for modification. Manipulation of the manikin was achieved by inserting an NGT through the manikin’s nose, pulling the tip of the NGT through the trachea (following visualization with a laryngoscope) and through the chest cavity. This allowed the NGT tip to sit outside the manikin and the chest block to be put back (Figure 1). The NGT tip could then be inserted into various prefilled syringes and blue-tac® was used to create a seal, in order to avoid leaks. These pre-filled syringes were obscured beneath a sheet or blanket.

Modified manikin model

A staff member could set up the desired solution in the syringe prior to the parental education session and the manikin could be dressed and/or wrapped in a blanket to ensure parents could not see the second syringe filled with the solution. These syringes could be changed over quickly and easily at the foot end of the blanket, allowing different coloured aspirates to be obtained over the course of the education session (Supplementary Material: Video) depending on the educational objectives.

Water, formula, baby food and lemon juice were mixed to create solutions that would yield different pHs (Figure 1).

The neonatal nursing education team were shown the model and given time prior to the education session to familiarize themselves with the model and change the different types of pre-mixed aspirates. The model was then used in conjunction with a face-to-face parental education session with discussion and explanation of NGT feeding with parents of neonatal patients. The modified manikin was used in a pilot of four sessions over 2 months (each session lasting up to 30 minutes) which were attended by 15 neonatal parents. Parents who had a baby admitted to the neonatal unit could choose to attend the education sessions. There was no commitment for them to complete the feedback form about using the modified manikin.

The theoretical discussion around indications and how to insert an NGT was kept at the beginning of the session. Staff would then give a demonstration of the insertion and pH testing process on the manikin. The NGT insertion process was performed using an unmodified manikin (removing the need for the NGT to be passed via the trachea which is required in the modified manikin to allow aspirates to be obtained) and then the training for obtaining and checking the aspirate was performed using the modified infant manikin. Following this, parents were able to spend much of the session practising measuring, inserting and checking the NGT using the unmodified and modified manikins, respectively (switched at the appropriate moment by the education team), and troubleshooting any issues, for example, mucky aspirate management, with the staff member leading the session.

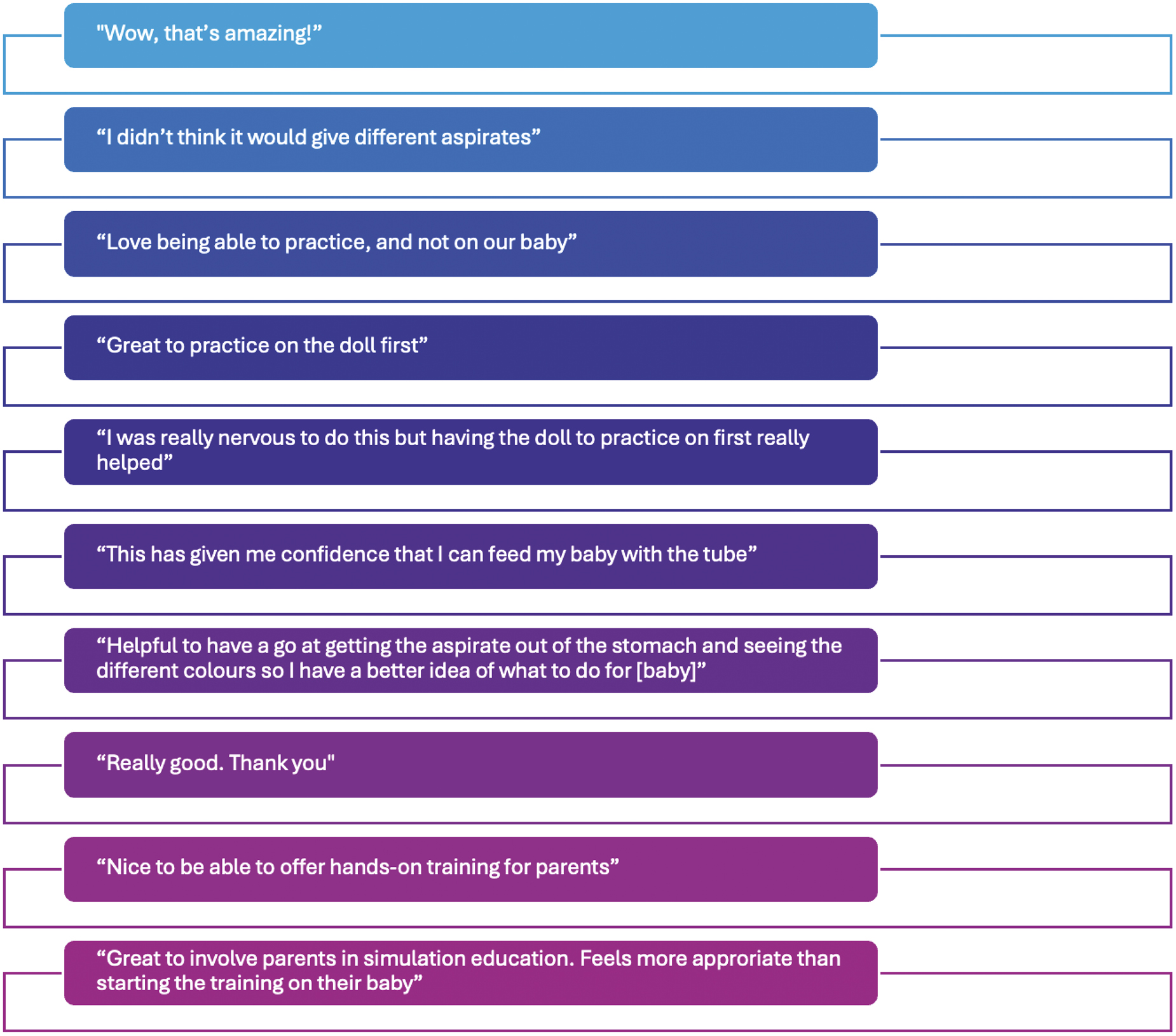

Free-text written feedback was gathered following a parental education session from both the parents and staff present (Figure 2). Feedback was gained from nine parents and four members of the neonatal nursing education team. The parental feedback was gathered through both verbal comments and written evaluation. This feedback from parents was positive, stating that they appreciated being able to practise on the manikin, before trying an NGT feed with their own baby. Staff performing the parent education sessions also gave the modified manikin positive feedback, reporting that they felt it made the session more realistic and would be a helpful aid to support parental education and confidence. Hundred per cent of respondents stated that using the manikin to obtain the different aspirates was helpful.

Qualitative parental and staff feedback

This modified manikin model is easily set up and portable. Initial feedback indicates the modified model makes NGT education sessions more real, relevant and engaging. Learner engagement is key to information retention and helps to increase parental confidence and motivation.

The manikin modification described in this article outlines how simple, low-tech and reversible modifications of existing simulation manikins can enhance parental education. This modification is a proof of concept, and, as such, has not evaluated any long-term impact on parental education. This would be an interesting area for future research.

The author would like to thank the parents and neonatal nursing staff involved for participating in this project.

None declared.

Nil to declare.

No further data to share.

The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.