Limited opportunities in clinical practice result in student midwives feeling ill-prepared to care for bereaved parents experiencing baby loss. Bereavement simulation is an effective pedagogical approach. Evidence for its effectiveness as a transformative teaching strategy to prepare students for this aspect of care is limited

To explore student midwives’ experiences of caring for bereaved parents within a simulated setting.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis was applied to gain insight into the students’ lived experience. Mezirow’s transformative learning theory (TLT) was used to assist students to critically reflect on the simulation.

The study was conducted at a Higher Education Institute in the Northwest of England. Nine third-year student midwives participated in a performance-based simulated scenario.

Data was collected using semi-structured interviews and analysed following Interpretative Phenomenology’s heuristic framework

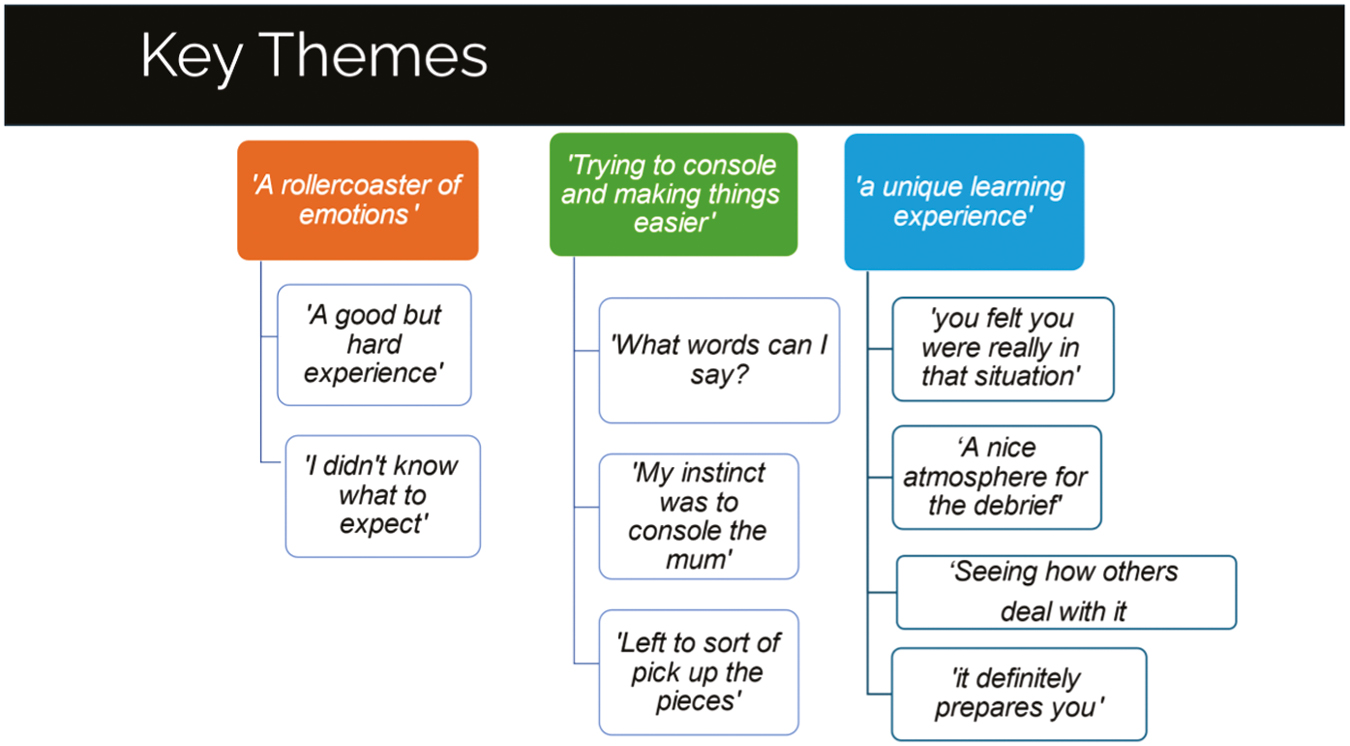

One of the generic themes identified, included ‘a unique learning experience’ and its related sub-themes ‘you felt you were really in the situation’; ‘a nice atmosphere for the debrief’; ‘seeing how others deal with it’, and ‘it definitely prepares you’, characterised the transformational learning process the student underwent after initially encountering bereaved parents. The simulated scenario represented a disorientating dilemma which they found challenging. Through critical self-reflection, students altered their perspectives about grief and loss and integrated new knowledge and skills that they could apply to caring for grieving parents.

Performance-based simulation is a creative approach to bereavement education that can prepare midwifery students to embrace the complexities of grief and loss and holistically support bereaved parents in their journey of grief.

Midwifery students need to apply the theoretical knowledge learned in the classroom to all aspects of midwifery practice to ensure that women and their families receive safe, high-quality care [1]. However, bridging the theory–practice gap in bereavement care and baby loss is challenging. Evidence suggests that healthcare staff including student midwives lack the necessary knowledge and skills to support and communicate with bereaved parents emotionally [2].

There are limited opportunities for midwifery students to care for bereaved parents. Many are protected from such complex events in practice [3]. Consequently, they feel anxious and struggle to emotionally support grieving parents [4].

Within undergraduate midwifery curricula, there is still considerable emphasis on theoretical approaches to bereavement education [5]. This is despite the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s (NMC) recommendation that student learning should be facilitated using a diverse range of methods, including simulation [6]

A survey of tertiary education examining stillbirth education for student midwives reported inconsistencies concerning the content and method of teaching [7]. A mixed-methods study exploring pre-registration midwifery education also emphasized the ‘normality’ of birth. Perinatal loss was represented as an unexpected event in childbirth as opposed to a potential adverse outcome in the continuum of pregnancy and birth [8]. Therefore, standardizing undergraduate midwifery education including simulation is crucial.

Simulation is an effective pedagogical approach, particularly concerning situations involving unexpected death [9]. Combining theoretical and experiential learning using simulation can bridge the gap between theory and practice and complement other teaching and learning strategies [10]. Well-structured bereavement scenarios incorporating key elements including a disorientating dilemma (an uncomfortable critical event), critical reflection and rational discourse can support the transformative learning process [11,12]. In simulation, through debriefing learners can challenge their pre-existing beliefs and assumptions, critically reflect, and seek alternative ways to how they may approach and problem-solve a complex situation[13]. These aspects underpin the transformative learning process [14].

Education on death and dying is pivotal in preparing midwives and nurses for these catastrophic events in practice [15]. However, there is limited evidence related to bereavement simulation as a disorientating dilemma in promoting transformative learning and its application to practise within undergraduate midwifery education. This paper aims to address this knowledge gap.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was adopted to uncover how the students interpreted the simulated experience[16]. IPA is underpinned by the concept of double hermeneutics, involving the researcher trying to understand and make sense of the participants’ interpretation of their experience [17]. Mezirow’s model of transformative learning theory (TLT) was used as a lens to aid understanding and interpretation of the student’s experiences (Table 1). Through the process of critical reflection, learners acquire new skills and alter their perspectives which underpins the transformative learning process and the goal of simulation [11].

| Mezirow’s 10-phase process of Transformative Learning | Application to student midwives’ experience of participating in bereavement simulation |

|---|---|

| Experiencing a disorientating dilemma (A significant life event, crisis, death) | Student midwives encounter bereaved parents experiencing perinatal loss within a simulated setting |

| Undergoing self-examination accompanied by feelings of fear, anger and shame | Students re-examine their existing beliefs and assumptions about grief and loss which results in them questioning their own beliefs, feelings and values about death |

| Conducting a critical assessment of their own internal assumptions and beliefs; experiencing a sense of alienation from traditional social expectations. | When students consider their new view of the topic, it conflicts with their previous personal, professional or cultural assumptions, resulting in feelings of anger, fear and blame |

| Relating discontent to similar experiences of others – awareness that the problem is shared | Students engage in dialogue with their peers; recognition that others share similar feelings and responses to this experience |

| Exploring options for new ways of acting | Students consider new ways of applying their knowledge, skills and behaviours, which encompasses their new view as to how they would approach a similar event in practice |

| Building competence and self-confidence in new roles | Students plan ways to increase confidence in their ability to apply new knowledge and skills to different situations |

| Planning a course of action | Students acquire knowledge and skills to implement plans and strategies for action |

| Trying out new roles and behaviours | Students actively seek new knowledge and skills to implement a plan to guide their future actions |

| Developing skills and confidence in new roles | Students assess and try out new roles which are reflected upon and modified as required. |

| Incorporating behavioural change based on new knowledge and perspectives | Students incorporate new/existing knowledge and skills with new insights and understanding of their practice |

The recruitment process began by circulating information about the study via the university Blackboard site. The students were also informed via email about the study. Second- and third-year students in their last trimester wishing to participate were invited to contact the researcher via email or telephone. A face-to-face meeting was undertaken to discuss what the study involved. The students were given information sheets detailing the aims and purpose of the study. Consent forms were also distributed to the students. Nine female students participated in the study who were White, British, aged between 20 and 35 years. In phenomenological studies, small sample sizes are appropriate for gaining in-depth exploration of an experience [17].

The simulated experience consisted of an unfolding scenario involving parents who presented to triage with a history of reduced foetal movements at 38 weeks gestation (see Table 2 for sample scenario). The scenario was developed collaboratively with the midwifery lecturer and a specialist bereavement midwife and reflected a real clinical situation experienced by the students [18]. Before the simulation, the students had lectures on bereavement care, including a bereaved parent discussing their experience of baby loss.

| Bereavement simulation scenario |

| Holly is 38 weeks pregnant with her first baby. She attends her local maternity unit with her partner Ben as she is concerned because she has not felt the baby move for the past 24 hours. Following an initial assessment, the student midwife could not detect a foetal heart with a pinard’s stethoscope. |

| The simulation will encompass the ongoing care that the couple will require from the initial diagnosis confirming the baby’s death to the birth seeing and holding the baby and the ongoing support required. |

| Learning objectives |

| Understand the key components involved in communicating sensitively with bereaved parents. |

| Acknowledge the importance of individualized care and support for Holly and Ben. |

| Develop confidence in supporting Holly and Ben to make informed choices about what happens to them and their baby, including creating memories, funeral arrangements and ongoing support. |

| Recognize the impact of pregnancy loss and the death of a baby on healthcare professionals and know how to access good support for you and your colleague’s well-being. |

| Initial handover given to students |

| Stage 1: Initial triage |

| Holly’s pregnancy has been uneventful so far. She is now 38 weeks gestation. She conveys she has not felt any movement in her abdomen in the last 24 hours. She is in the waiting room. |

| This stage involves the Triage Midwife handover of the couple to the students. Student midwives are expected to conduct an initial assessment of Holly and find it difficult to locate the fetal heart. |

| This concern is then escalated to the Triage midwife. |

| Break for a debrief |

| Stage 2: Breaking of bad news |

| In this stage, the doctor is contacted, and an emergency abdominal ultrasound is undertaken. The couple is informed that there is no fetal heartbeat and that their baby has died. Students will witness the breaking of the sad news. The triage midwife is now present. |

| Break for a debrief |

| Stage 4: This stage involves the couple’s reactions and responses to the news. The couple are now left to consider the diagnosis of the baby’s death. It may demonstrate different ways in which a couple may react to the news and grieve. The students are expected to respond to the couple’s questions and concerns. |

| Break for a debrief |

| Stage 5: Now that the baby’s death is confirmed, a discussion takes place with the doctor about birth options regarding birth to include induction of labour. |

| In this stage, the couple may request a caesarean, it will depend on what they say. There may be questions posed about what the baby may look like when their son or daughter is born. |

| Break for a debrief |

| Stage 6: The baby now has been born. Holly and Ben consider meeting the baby and creating memories. At this stage, the couple may be reluctant to meet and see their baby. |

| Break for a debrief |

| Stage 7: This stage focuses on the importance of creating memories and a memory box. There may be a discussion of post-mortem, postnatal care, bereavement support agencies and funeral planning. |

| Final debrief |

Two simulated participants (SPs; both with acting backgrounds) were recruited to portray these parents [19]. We decided to adopt SP methodology as the simulation modality to promote a sense of realism and authenticity. The SPs were specifically trained to achieve the educational learning outcomes of the simulation scenario.

To promote the psychological safety of the learners, a combination of pre-briefing and debriefing opportunities was included [20]. In this study, ‘The Diamond Debrief Model’ for simulation was used to guide the pre-brief and debrief processes [21] (see Figure 1). It consists of structured questions and prompts designed for each phase of the debrief from the initial description of what happened followed by more in-depth analysis and application to practice.

![The Diamond Debrief Model of Simulation [21].](/dataresources/articles/content-1743669621703-a2a7acb6-340d-4538-812f-cad1f2b05ad4/assets/xqhm2627_f0001.jpg)

The Diamond Debrief Model of Simulation [21].

Data were collected via semi-structured, individual, face-to-face interviews (lasting 45–90 minutes) and audio recorded. The interviews were conducted in the counselling suite by the author on the university campus in the subsequent 2 weeks following the simulation.

The data from the interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed following the six stages outlined by Smith and Flowers [22] (see Table 3 attached). The Consolidated Standards for Reporting Clinical Trials (CONSORT) was adapted to promote a comprehensive rigorous process for the methodological approach, data analysis, interpretations and findings [23].

| Stage 1 | Reading and re-reading each individual transcript | Become familiar with the transcript and immersed in the participant’s world |

| Stage 2 | Initial noting (or exploratory coding) | Note the participant’s content, linguistic interpretations, and conceptual or interpretative comments relevant to research question |

| Stage 3 | Developing emergent themes | Analyse the exploratory comments to identify/generate themes that reflect participant’s words and researchers’ interpretation |

| Stage 4 | Searching for connections across emerging themes/ map themes together | Explore the emergent themes to develop a superordinate theme structure that captures the most interesting and important aspects of the participant’s account |

| Stage 5 | Moving to the next case | Repeat the process for subsequent cases |

| Stage 6 | Looking for patterns across cases/move to a more theoretical level of analysis. | Create a master table of the superordinate themes and related subthemes that capture the higher-order concepts shared across all participants. |

Ethical approval was granted by the University Ethics Committee. To safeguard the participants, ethical principles including informed consent, confidentiality and anonymity were strictly adhered to. As a lecturer, I was known to the students, so they needed not to feel coerced or obliged to take part in the study. The students were reassured of the option to withdraw from the study without any consequences. Professional midwifery advocacy support, counselling and additional follow-up support were also accessible at any time for the students.

Reflexivity is an approach that explores the relationship between the researchers [24]. As the researcher and a midwifery lecturer, I was already known to the students and had to acknowledge my assumptions, pre-suppositions and biases so as not to influence the study. I used a reflexive journal throughout documenting my thoughts and positioning within the study and discussed them with my supervisors. As the study progressed, I revisited these aspects and reflected on my role and influence on the study as well as honouring the students’ perspectives and stories [25]. In the final write-up of my study, to ensure transparency, I documented reflexive insights that communicated my feelings, perspectives and interactions with the students.

This paper reports on findings from a larger PhD study focusing on student midwives’ lived experience of caring for bereaved parents using simulation. Three themes originally emerged: ‘a rollercoaster of emotions’; ‘trying to console and making things easier’ and ‘a unique learning experience’. This paper reports on one of the generic themes that emerged: ‘a unique learning experience’ and its related sub-themes ‘you felt you were really in the situation’; ‘a nice atmosphere for the debrief’; ‘seeing how others deal with it’ and ‘it definitely prepares you’. The themes illustrated the students’ transformative learning journey as they critically reflected on their learning enabling them to apply the simulation experience to future practice. Figure 2 reflects the super-ordinate themes and related sub-themes as they emerged.

Group Experiential Themes and Subthemes.

You felt you were really in that situation.

The realistic nature of the simulated scenario was the main factor influencing the students’ ability to engage in the simulation. A high level of authenticity was created using SPs within a simulated setting enabling the students to fully immerse themselves and feel like it was a real event.

It felt so real, I could just picture myself in practice and with that happening (STM1).

Another student said it caused her to behave or respond as if she were in a real situation.

When I was actually in the room …, you think, oh god, it completely changes you when you’re there, you’re talking to them, you’re seeing them, they were such good actors like you felt you were really in that situation (STM2)

The realism and the authenticity of the scenario were surprising to the extent that the students ‘forgot about being watched’ and feelings of anxiety seemed to diminish once entering the room.

I was a bit like, oh my God, we are going to be watched’, then as soon as you step in, it all goes, you don’t think about what else is happening anywhere else and the University, or in the rooms, or in the corridor outside; you just think about this couple that are in front of you (STM3).

For others, the realism was so profound that it felt like ‘they were actual parents that had just lost a baby’.

It didn’t feel you were in the room, it didn’t feel like a simulation, it felt like they were actual parents that had just lost a baby, I walked out, and I was like, I cannot believe that was a simulation, you’re focused and, in the moment (STM4)

The students described that simulation as ‘a unique learning experience’. The sense of ‘being in there and thinking and you’re in there with the parents’ implied a sense of connection with the parents. Comparisons were made with the classroom situation ‘whereby just talking about how you would deal with it’ suggesting a more passive approach to learning.

It was a unique learning experience for me and it’s so much different to being in the classroom and just talking about how you would deal with it. And being in there and thinking, oh this you know, you’re in there with the parents and it’s completely different (STM3)

A nice atmosphere for the debrief.

The students valued the opportunity to debrief and reflect on the experience within a supportive and trusting environment. They talked about sharing this deeply emotional experience with their peers and how it felt supportive which is key to transformative learning.

The discussion after, the kind of in between, and everyone was supportive and they were like, would you have said that in this situation, and I think it was that kind of analysing or the bit after (STM6).

Learning through simulation enabled the students to confront and test the limits of their capabilities and there was some evidence that in instances ‘where you might not have said the right thing’, it felt reassuring that there was no blame’ (STM1). The opportunity of having a safe, secure environment in which to make mistakes was in stark contrast to the clinical setting, whereby making mistakes was not always viewed positively.

When we spotted mistakes that others had done like we knew that’s how it is in midwifery like you pick up the best from people, not like you think, oh I would do that differently and there was really good support for each other, it’s a safe environment to do so. Unfortunately, you’ve not got it in practice (STM6).

The students acknowledged that when the environment feels safe, they are more likely to feel accepted and their contribution to the discussion was well received. One student talked openly and truthfully about mistakenly reassuring the bereaved mother saying that ‘there is nothing to worry about’ and then she said, ‘and that’s what she picked up on’.

because if I made that mistake in practice, saying the wrong words in practice, that would be worse, whereas there, I felt all those emotions, but actually, it was, it was okay; and everybody will have learned from that as well, the same as, you know, I’ve learned some, what looked like good practices, people have learned from, you know, other mistakes that have been said (STM7).

For this student, ‘saying the wrong words’ provoked feelings of self-blame and worthlessness. However, on reflection, she appeared to have gained a deeper understanding and a new meaning perspective. She reflects on how ‘they (her peers) will have learned from that as well’ which implies a belief and value about her self-worth and a sense of openness to new meanings.

The vital role of debriefing throughout the simulation was repeatedly emphasized as a valuable learning experience. The sense of ‘being part of a small group’ and ‘being with them’ and having group familiarity was considered a strength and generated a sense of professional bonding and emotional support from the experience.

‘Being students, they understand that we haven’t got all the answers, and we haven’t got all the skills, it’s quite nice that you can relate to your peers…… ‘Everyone, like people, makes mistakes, it was just, I don’t know, I just thought it was nice, especially because it was quite a small group, it was a nice atmosphere for the debriefs’’(STM8).

‘Seeing other people deal with it’.

For many students, significant experiential learning was gained from observing their peers and the opportunity to ‘pick from other people’s experience’ stimulated them to reflect upon their own learning needs and incorporate new ways of thinking and practicing. The students talked about ‘taking bits away …. as to what might be a good thing to say and having a little speech’ prepared almost like an aide memoir to help them in a similar situation.

‘Watching them I thought, I kept taking bits away, thinking, oh yeah, that’s a good thing to say, or that’s the useful thing that I could have in like a little speech sort of, you know, if I was in that situation’ (STM9).

Through observing their peers, they gained an insight into professional role-modelling behaviours which they felt they could emulate and be a point of reference for future care and practice.

’It was so good seeing some of the others and how they spoke, their tones of voice and all that was so good because you can learn from that. … yeah, I think so, it’s good to have watched what everybody else did, because you can learn from them. yeah. I don’t think you’d learn much if you didn’t watch everybody else’ (STM8).

The students’ ability to critically evaluate their new roles and behaviours was enhanced by observing their peers’ knowledge, skills and caring behaviours. This empowered them to reflect on and assess aspects of care they had not thought about previously. The excerpt below describes the caring practices observed and notes how their peers were responsive and adaptive to the holistic needs of the parents.

‘Seeing some of the others it was, it was nice, because they included like dad and the way that they spoke about baby, and you know, she’s beautiful, she looks like you and that kind of thing, it was really, really nice to see. Yeah (STM4).

Another student commented on how much she gained from observing each of her peers and how her professional role could be shaped by others.

‘I think was and watching how everyone else reacted, and you can take things from each person. It’s like when you work with different mentors, you take a little bit of something from all of them to make who you want to be, and I think it’s like that with your peers as well’ (STM4).

This sub-theme indicates that through observing their peers, the students were able to redefine the experience from different perspectives and critically evaluate significant aspects of care they would incorporate into future practice.

‘It definitely prepares you’.

The students reflected on how the simulation might emotionally prepare them and enable apply their new knowledge and skills to caring for bereaved parents or a similar event in practice. One student talked about gaining skills and ‘learning to cope with the “emotional side of things” and how to comfort’. She goes on to say:

‘It definitely prepares you that way and then the emotional side of things, it does prepare you for how to react and how to comfort, yeah’ (STM9)

Other students found participating in the simulation helped them apply different skills to different aspects of care.

‘How you would do, like from stage to stage, so from being told, the baby’s died to then the postnatal care and how you can use your skills in each different situation, like along the journey’. (STM2)

For others, the outcome of the transformative learning process resulted in them having the belief and confidence that they would know what to do and what to say.

‘But that’s what is good about simulation, is that you had that chance to kind of, almost practice it so then when we go out, if it does happen, or in any kind of situation where something happens, you know kind of know what to do and to say a bit better. It made me think about how I reacted in that situation and how I might change how I’d behave in the future’ (STM3).

Others reflected on how the simulation provided them with the confidence to ‘become more involved’ and the importance of presence in supporting the bereaved couple. They articulated confidence in their ability to provide emotional support to the bereaved parents and an intuitive sense of self-awareness as to what to do.

‘I think drawing on that experience now, I think I’d be a lot more involved. Maybe kind of sitting by them, spending more time with them, but before, if my mentor left the room, I left the room. Now I would be able to sense what they wanted’ (STM9).

The excerpt above describes the student’s sense of moral agency and satisfaction in being able to invest the time and effort to emotionally support the couple. The simulation helped the students to have a positive view of themselves and a belief they could make a difference.

Transformative learning can ‘set in motion’ new ways of thinking and behaving. The simulation empowered students to have a holistic understanding of their clients’ needs, their professional roles and how care should be provided. The following excerpt illustrates a student’s new perspective as to how the ‘simulation helped her to read the situation’ after she was involved with two women who experienced baby loss. The narrative reveals a sense of empowerment to do things differently or to behave differently. There was a reference to ‘trying not to put your own opinions forward about what the parents would like’ which indicates a new understanding of the parents’ rights and choices about making memories for their deceased baby:

‘When I was doing a bank shift, we had two ladies that had sadly lost babies; one quite early on, and one later, and I think that simulation helped to be able to read the situations …….and like what you’d do in that kind of situation, and you know, don’t forget to include the partner or things like that. Trying not to put your own opinions forward about what the parents would like, you know like the pictures and holding baby and that kind of thing’ (STM4).

The students identified aspects of the simulation that they felt they could utilize and apply to the care of bereaved parents. However, despite participating in the simulation, there was a sense that nothing could ever prepare them for such an emotional event. The following extracts illustrate the students’ ongoing sense of anxiety and uncertainty about coping with stressful events like perinatal loss.

‘It definitely would relieve some anxiety about being in that situation again’, ‘I’d still feel worried …’ ‘But I’d feel a bit better having done the sim’ (STM9).

Along a similar theme, another student stated.

‘I don’t think you can ever be fully prepared or ready for something like that’. However, she refers to the simulation as ‘a stepping stone’ and felt ‘it was quite a good, sort of like first stepping stone to, something like that’ (STM1).

This paper aimed to explore the students’ transformative learning experiences of caring for bereaved parents within a simulated context. The students found the simulation to be disorientating. Nevertheless, it enabled them to acquire knowledge as well as gain a deeper understanding of their own professional identity and ability to communicate with the bereaved couple. Through the process of self-reflection, students were able to make meaning and explore a new set of expectations and perspectives about the reality of what it feels like to be in a stressful situation involving death [9]. This transformed their learning about caring for bereaved parents for the first time [26].

Mezirow theorizes that, once learners experience a disorientating dilemma, it can trigger a ‘deep structural shift’ in their thoughts, feelings and actions [27]. For this to occur, students must be afforded learning opportunities like simulation that encourage them to actively engage in their learning and stimulate them to become independent, critical thinkers [28]. To enable students to become clinically proficient, highly skilled, experienced educators need to create authentic learning experiences that reflect the complexity and ambiguity of the real clinical setting and provoke feelings and emotions similar to those in a real-life situation without causing undue distress or shame [29–31].

For the students in this study, the realistic nature of the simulation proved to be significant. Other studies suggest that physical, emotional and contextual realism and a sense of ‘being there’ are critical attributes of simulation. These aspects enabled the students to immerse themselves in the simulation, which ultimately helped to achieve their learning outcomes compared to traditional methods of teaching [29,32]. Incorporating simulated participants who can display emotions and non-verbal forms of communication ensures that students can become proficient in the affective domain of learning [33]. These findings support other studies acknowledging the value of simulated participants in decreasing students’ anxiety and increasing their confidence, particularly around end-of-life care [34–36].

The aim of this study was not to measure the impact of simulation on clinical behaviour and transfer to practice. Nevertheless, a significant finding was that the students perceived simulation as a ‘stepping-stone’ to prepare them for similar events in practice. The students alluded to having the courage to know what to say and do in future situations. The simulation enabled them to cope with the emotional aspects and how to provide comfort. They felt confident to apply their skills to different situations. Changed attitudes and increased self-confidence influenced the transfer of their knowledge and competence to clinical practice. This adds to existing evidence on bereavement simulation as an active learning approach to reducing students’ anxiety and providing them with the courage and confidence to provide such care [37,38].

Despite the initial turmoil associated with perinatal death, this study illustrates how a stressful childbirth event can be a powerful stimulus for professional growth and learning. More recent studies confirm that despite the personal and professional heartache associated with experiencing traumatic events in practice, midwives and other healthcare professionals still gain personal fulfilment and a deeper insight into their personal competence and confidence to provide quality bereavement care [9,39].

The experiential nature of the simulation combined with debriefing, and critical reflection enabled the students to process their feelings about grief and loss from a more complex perspective and prepare them for the human experience of life and death in a real clinical situation [9]. The students’ perceived confidence in being able to incorporate changes into their practice and reconstruct their own identity as compassionate caregivers indicates transformational change and aligns with Mezirow’s transformational learning framework [14].

The students’ narratives indicated a meaningful change in their understanding and belief about grief and loss, and how to provide emotional support. They attributed this to observing their peers and learning from them. Bandura’s social learning theory asserts that learners gain valuable insights and confidence through observing and role-modelling the behaviours of others [40]. It also confirms the powerful impact of peer learning in simulation. By witnessing positive caring attitudes and practices, such as cultural sensitivity, compassion and emotional intelligence, simulation can transform students’ awareness of the importance of caring enabling them to become competent, caring practitioners in the future. This underpins the principles of moral education [41–43]. These findings align with the concept of situated learning that stresses the importance of students participating in authentic learning experiences. [44]. Through dialogue and engaging with others in a ‘community of practice’ can initiate a change in perspective and shape their understanding by challenging their existing views and opinions, and creating new knowledge through critical reflection [27,45].

In this study, the students valued the opportunity to engage and reflect with their peers who shared the same experience and could relate to it [46]. Other studies confirm the value of students having a shared dialogue with their peers to discuss a common experience [46]. This encourages feelings of belonging and connectedness and such conditions enable transformative learning to occur [47].

Caring for bereaved parents is a clinical reality for many students and healthcare professionals and incurs enormous emotional pain for all concerned [48]. Whilst simulation can never fully capture the true reality of grief and loss, for the students in this study, it offered a ‘unique learning experience’. They described simulation as very different from sitting in a classroom and ‘just talking about it’, which suggests that didactic or inquiry-based learning methods of teaching are not effective in preparing students for end-of-life care [49]. The experiential nature of learning through simulation provided the students with a belief and sense of self-efficacy in their ability to embrace similar challenging situations in the future. These findings concur with other studies about the importance of developing students’ resilience using different pedagogical teaching approaches including simulation [50].

Even though the scenario presented challenging concepts about grief and loss, their narratives revealed a determination to improve their practice and make a positive impact on the future lives of bereaved parents. These beliefs and attitudes signify a transformational growth in resilience and facilitate a transition to capable, kind, compassionate caregiving [51].

There are inconsistencies and a lack of a standardized approach to bereavement education within undergraduate midwifery education, both nationally and globally [48]. This causes students to feel ill-prepared and anxious when they encounter parents for the first time and can impact care [52]. Within undergraduate midwifery programmes increased exposure to simulated scenarios, with varying degrees of complexity, will ensure students develop the full scope of midwifery knowledge and skills to provide holistic, compassionate care to bereaved parents [6]. Furthermore, the lack of exposure to perinatal grief and loss experiences in practice can be rectified by the integration of continuing bereavement education and training using simulation for all healthcare professionals to ensure emotional preparedness for practice.

Health Education England Work Experience Quality Standard Framework stipulates that students in clinical practice should be appropriately supervised and have opportunities for reflection and debriefing [53]. Therefore, exposure to critical incidents should ensure that students are well supported and receive adequate supervision and debriefing to mitigate any long-term psychological and emotional trauma associated with these events.

There are a limited number of studies that specifically address end-of-life care simulation and perinatal loss involving student midwives. This highlights the need for further qualitative research and longitudinal studies evaluating students’ experiences and whether this results in increased emotional preparedness for practice and improves care for bereaved parents in the long term.

Further research is also needed to evaluate the extent to which bereavement simulation results in a changed or altered perspective on students’ beliefs, assumptions and attitudes towards grief and loss.

This study utilized a small convenience sample size of undergraduate student midwives from one university, limiting replication of the findings to students from other university locations. The sample of students was female mainly White and British and may not reflect the experiences of other students from diverse ethnic, cultural and gender backgrounds. The study only addressed the transformational learning of the students at the point of interview and did not address the impact of the simulation on actual application to practice. Finally, the students self-selected to participate in the study which may potentially bias the findings due to having a special interest in bereavement care.

Encountering bereaved parents experiencing unexpected baby loss is a disorientating and bewildering experience for many students. If they are not offered opportunities to emotionally process emotive and complex events like death, they may not be proficient in fulfilling their future role to provide compassionate care to bereaved parents. Considering the emotional nature of midwifery and the trauma they may encounter in practice; midwifery curricula must be underpinned with trauma-informed care specific to perinatal loss and incorporate simulation as an adjunctive to prepare students to provide relational caregiving to grieving parents and their families.

Dr. Anne Leyland- Conceptualisation; including methodology; data curation; analysis and writing.

None declared.

None declared.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee, University of Salford.

None declared.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.